The village Kavele, as it was even called in later times by Yiddish speakers, was known since the beginning of the 14th century as a crossroads on the way from Lithuania to Ruthenia, the lands populated by eastern Slavic peoples. Kovel obtained its status as a city in 1518. It was in the district of Volhynia, then part of the Duchy of Lithuania which was establishing itself as a dominant power among the principalities that had been part of the Kievan Rus' dynasty. During the next century, the Jewish community fared reasonably well as far as their rights and economic influence. But tensions from economic competition, anti-Semitism and crusades against heretics led to worsening conditions in the 1600s with complaints by Kovel burghers to the king and, in 1648, the Cossack-led Chmielnicki massacres. The late 19th and 20th century saw the growth of a vibrant Jewish community - economically, politically and intellectually - but the rapid succession of World War I, the Bolshevik-Polish war and becoming part of a reconstituted Poland, with its waves of virulent anti-Semitism, had devastating effects. The Soviet occupation in 1939 effectively ended Jewish community life, and the occupation by the Nazis which quickly followed, wiped out the Jews of Kovel. The anguish of many of those who lost their lives was recorded in nearly 100 pencil-written notes on the walls of the city's Great Synagogues, lamenting the dead, asking remembrance and calling for vengeance on the Germans.

Jews had lived in parts of Lithuanian territory since as early as the eighth century. Some came from south Russia, and later in the 12th century, German Jews started to immigrate in part because of persecution by the Crusaders.

A chapter in the Kovel Yizkor book, published in 1957, quotes an article from the weekly Hebrew newspaper HaMelitz in 1893 on the history of Jews in Kovel in specific:

In our estimation, Jews settled in this area approximately 500 years ago. Although there is no direct evidence of this, there is the evidence of graves and remnants of ancient tombstones in the cemetery. To this day, there are ancient tombstones in the Ancient Cemetery (there are three cemeteries here: the New, the Old, and the Ancient), some at least three hundred years old, and doubtless what was intended to be a monument simply collapsed into a heap of ruins under the weight of the years. It could be that they were first put there at the time the first Jews arrived in the area."

Volhynia had belonged to the House of Rurik, the ruling dynasty of Kievan Rus' or Red Russia, the area that is now largely modern Russia, Belarus and Ukraine. This dynasty probably owed its origins to Norseman and Vikings who moved eastwards and southwards into those lands.

By the middle of the 12 the century many of the lands over which Kiev Rus' had held sway gave way to independent principalities. Poland conquered Volhynia in 1074.

The Lithuanian-Polish Era

At the beginning of the 14 the century, Gediminas, the Grand Duke of Lithuania, captured Volhynia from Poland. Poland at the time was ruled by a branch of the Geminids known as the Jagiellons and, later in 1385, both states formed a dynastic union through marriage in which they were governed by the same ruler but maintained their own boundaries and interests.

The Jewish population appeared to prosper under Gediminid and later Jagiellon rule and took an active part in development of new cities. They grew in enough numbers and influence to obtain privileges from their Lithuanian rulers. Grand Duke Witold (also known as Vytautas) granted a charter of rights to the Jews in 1388. The preamble read:

In the name of God, Amen. All deeds of men, when they are not made known by the testimony of witnesses or in writing, pass away and vanish and are forgotten. Therefore, we, Alexander, also called Vytautas, by the grace of God Grand Duke of Lithuania and ruler of Brest, Dorogicz, Lutsk, Vladimir, and other places, make known by this charter to the present and future generations, or to whomever it may concern to know or hear of it, that, after due deliberation with our nobles we have decided to grant to all the Jews living in our domains the rights and liberties mentioned in the following charter.

The charter established the basis for the legal status of Jews, including freedom of trade and worship. .

Much as was the case with the Emperor Franz Josef who was considered, and even revered, as a benevolent ruler to the Jews in Galicia during the late 19th century when it was part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, Witold's treatment of the Jews endeared him to them. The Jewish Encyclopedia says that "for a long time traditions concerning his generosity and nobility of character were current among them."

Jews also fared well under the Jagiellon ruler Sigismund I, who was both King of Poland and Grand Duke of Lithuania in the first half of the 1500s. He relied on the services of Jewish "tax farmers" who would pay the taxes for certain areas in exchange for giving them rights to cover their outlays by collecting money and goods in that area. In 1507, he confirmed the grant of privileges made by Witold more than a century earlier.

Around 1539 or 1540, rumors spread, abetted by an accusation by a baptized Jew that Jews were kidnapping or buying Christian children, converting them to Judaism and smuggling them to Turkey. Another historical source describes the accusation as saying the Jews were also killing or circumcising Christian children. Sigismund ordered an investigation that found nothing but his nobles carried out a series of arrests, house break-ins and other abuses. The next year, Jews of Kovel and other Lithuanian towns protested to Sigismund, and after a special commission upheld their protests, Sigismund declared them free of suspicion.

Relations Begin to Worsen

By the middle 1500s, relations between Christians and Jews began to worsen, initially because of economic competition and then by the animosity of the clergy who were engaged in a crusade against heretics, sparked in part by the spread of the Reformation from Germany that spawned the Lutheran and Calvinist movements. Kovel memorial book says:

As early as 1556, the people of Kovel appealed to Queen Bona to restrict the Jews of the city to living only in the street of the Jews. The Jews did not even enjoy the privilege they had been granted by the queen's son the year before which promised them freedom to live and work anywhere in the city, and which had first been granted them as early as 1547.

Queen Bona Sforza, the second wife of Sigismund who often wielded authority in the last years of his life, granted a petition from the burghers of Kovel forbidding Jews to reside in the marketplace, which also had the effect of excluding them from the census. The Queen also ordered that Christians give up any residences they lived in on Jewish streets.

Protests were made to the King who ordered the release of prisoners, but Kelemet initially refused, saying he was subject only to Kurbski's orders. After five weeks, Kurbski bowed to the orders of the king and released the prisoners and had the seals removed from the synagogue, houses and stores. But he warned that he would get satisfaction from the Jews at a future time. Kurbski continued to borrow money from Jews and died in 1581 still having not repaid many of his debts.

The economic tensions that had been simmering since the middle 16th century came into sharp focus in the next century. Christians of Kovel protested to the king in 1616 about economic competition from the Jews. The History of the Jews of Volyn, from a Polish Yizkor book, said most Jews were involved in crafts connected to religious observance such as butchers, tailors and weavers. They faced competition from the tzachim (Christian professional guilds) who, although weak in Volhynia, had some success in Kovel in 1617 with efforts to collect taxes from Jewish craftsmen and limit the amount they could produce.

Later, in 1648, Jews also found themselves victims of the ambitions of Bohdan Chmielnicki, a leader of a Cossack military band, who had aspirations of ruling the Ukraine. Chmielnicki began a revolt drawing on the frustrations of the sizable Slavic population that felt oppressed by the Polish-Lithuania union. The JewishEncyclopedia.Com describes how these two forces played out:

The burghers of Kovel complained to the king (in 1616) that the Jews bought up taverns and houses without having the right to do so, thus crowding out the Christians, some of whom had been reduced to beggary by the unjust exactions of the Jews; that the latter farmed the taxes imposed by the Diet, as well as private taxes; that by exacting enormous profits the Jews were ruining the town, in consequence of which people were removing from it; and, finally, that the Jews took no interest in providing for the repair of the walls and in guarding the town. The king appointed a commission to investigate the complaint, and to render a decision, each side to have the right to appeal to the king within six months thereafter. The resentment of the Christian merchants against their more successful Jewish competitors was intensified during the following thirty years, and found emphatic expression in the turbulent times of (a Cossack "hetman" or military commander Bohdan) Chmielnicki. In 1648 the magistrate of Kovel reported to the authorities at Vladimir that the local burghers had helped the Cossacks to drown both the Jews and the Catholics who had remained in the town, being unable to get away on account of their extreme poverty.

The Chmielnicki uprising was a devastating blow to Lithuanian Jewish communities, although the fact that they were a prime target was not a simple matter of anti-Semitism, but class warfare. Jews were the agents for the Polish ruling classes and the hatred that the Cossacks and Ukrainians had for them resulted from a combination of resentment over economic exploitation and nationalistic fervor. Nevertheless, Jews saw the massacre as an unprecedented outburst of anti-Jewish violence, and considered it a precursor of the Russian pogroms and even the Holocaust.

A complaint presented by the Catholic priest of Kovel said that all the Jews and Catholics who were unable to flee the city were drowned in the river.

How many Jews died is uncertain. Contemporary Jewish accounts put the number at around 100,000, but Richard S. Levy, writing in his book Antisemitism: A Historical Encyclopedia of Prejudice and Persecution, noted that "most recent historians have scaled back considerably the probably number of deaths, in part simply because the population of Jews in the eighteenth century could not have risen to the levels it did" if that number had died. The number of Jews in Ukrainian and Polish lands at the time of the massacres was 350,000.

In Kovel, those who returned to their homes afterwards were almost destitute. The community was reconstituted in 1650 under the protection of King Casimir, although the JewishEncyclopedia.com says that in 1661, there were only twenty Jewish house-owners in Kovel.

Kovel began to rise in importance as a community in Volhynia in the 1680s. by 1698, Kovel appeared to have become a leading Jewish community in Volhynia because one of the key players at a meeting of the Volhyn Council was the rabbi of Kovel, according to the History of the Jews of Volhyn. The Encyclopedia Judaica put the Jewish population of Kovel at 827 in 1765. This population comprised comprised 187 Jewish families; of those 137 were homeowners and the remaining fifty were tenants. The Kovel memorial book says 209 of the 827 Jews were described in a section of the census as being "abjectly poor, but says, "The truth is that the number of the poor was substantially larger than what was listed in the census, and it turns out that a decisive majority of the Jewish population of Kovel was poor, as was the case in other cities."

Kovel Passes from Polish to Russian Rule

Volhynia passed to Russian rule in the late 18th century after three partitions of Poland that were a result of the territorial ambitions of Russia and Prussia and which effectively ended the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth. During the second and third partitions of Poland (1793, 1795), Volhynia passed to Russia and was made (1797) a province. Kovel became Russian in the third partition.

Under Russian rule in 1799, there were 11 merchants, all Jews, and 811 Jewish citizens compared to a Christian population of 1,308, according to the Encylopedia Judaica. The Jews were allowed to select a deputy mayor. A history chapter in the Pinkas Hakehillot Polin - Volyn Vepolesia said that the Jewish population in Volhynia as a whole tripled during the first 50 years of Russian rule and cited the 1847 census as putting the number of Jews in Kovel at 9,029.

There was a fire in 1857 that destroyed synagogues and many Jewish homes, and many of the historial records, but the community quickly rebounded.

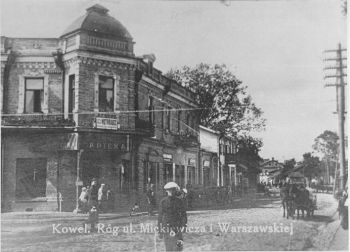

In the 19th century, Kovel became a commercial center. By the late 1880s, Kovel had been joined by rail with cities that all had sizable Jewish communities: Minsk, Warsaw, Siedlce, Kovno, Brest-Litovsk, Kiev, Grodno, Rovno, Proskurov, Mogilev (Podolsk), Kishinev, Bender, Odessa and Fastov.

The Kovel Yizkor book (1957) described the impact that the laying of the rail lines had on the city:

From the time the tracks were laid, the city threw off its old form and reinvented itself. Almost magically, wide, paved roads began appearing in the city, including the beautiful Beit HaNetivot Street, along which the houses were built in the new style. Next to the old city, whose aging houses were decaying and whose streets were small and narrow, there arose a fresh new city on the sands full of energy and beauty. Alongside the new houses and streets there arose a new Jewish settlement in the city, brimming with life.

The Yizkor book account gives much credit for the the growth of Kovel to Yaacov-Aharon Entin, a wealthy businessman, who was contractor for the railroad. Entin also invested "much of his wealth in large building projects, in order to provide income and occupation to the Jewish laborers in the city," according to the Yizkor book account. "That was the stimulation, the galvanizing force, which drove him to build the 30 large barracks for the 'Kovelski folk.'" Entin died in 1897.

The Jewish population was put at 8,521 by 1897, about half the city's residents (although other sources have somewhat different figures). In 1906-07, the American Jewish Yearbook put the number of Jews at 6,046 out of a total population of 17,403. In 1921, Jews accounted for 12,758 of the total population of 20,818. The 1921 census said there were 317 Jewish industrial enterprises (factories and workshops) which employed 654 people. Of them, 110 employed laborers. Of the people employed by the 317 Jewish factories were listed 311 homeowners, 47 of their family members, 288 Jewish workers (277 men and 11 women) and eight non-Jewish employees. The factories branched out into the following areas: the clothing industry - 309 people; leatherworkers - 60 people; food industry - 58 people; building - 49 people; graphics - 3 people; cleaning - 54 people.

The Yearbook also reported, in 1911, the death of Pincus Gonsarvosky, a tailor, at the age of 120.

Michal Friedman, who was born in Kovel in 1913, provided this feel for the culture and layout of Kovel in the 20s in a 2004 interview with Centropa.org, an organization that has interviewed over 1,300 elderly Jews since 2000 to record their stories of Jewish life in Europe and the impact of the Holocaust.

In our town tradition was kept up even by the few assimilated. On Yom Kippur there wasn't one case of anyone failing to come to the synagogue. On the other hand, in all the homes I knew, it was mostly the women that kept kosher. Because the communists, for instance, flaunted the fact that they didn't observe tradition. Kovel was a Jewish town whose outskirts, where the Ukrainians and Poles lived, formed a separate town. The river Turija flowed through the town. Kovel was divided into three quarters. On one side of the river there was the Old Town, called Zand [in Yiddish], or Sand, as it had been built on sandy ground. In the new part, on the other bank of the Turija, there was Kovel where the Poles lived, most of whom were employees of a railroad company, Depo; they repaired railroad cars and engines. That was a separate town. There were fewer Ukrainians than Poles there. Their farms began just behind the main street. Those three worlds lived side by side.In a town with twenty-something thousand residents, there were two coeducational gymnasia, a newspaper, Kovler Sztymer, and two Jewish clubs: the Sholem Aleichem club and the Peretz club. The Zionist organizations had their own clubs and libraries, too. And on the Jewish street a struggle pitting Yiddish against Hebrew raged. The town was relatively secular. Among its important institutions was a Tarbut Hebrew gymnasium and a local Poalei Zion organization, which, just like the Bund, stood for cultural autonomy for the Jews.

After 1918, a Jewish theater existed in our town, something that would have been impossible under the Tsars. It was an amateur theater; its actors were workers, teachers and students. The entire repertoire of Jewish classics was performed in that theater. It existed until 1st September 1939. Theaters from the capital visited us frequently too. Even [Alexander] Granach, the great actor, came to Kovel. And of course the Jozef Kaminski Theater. I didn't see The Dybbuk [16], but I did see Sholem Aleichem's ‘The Grand Prize' and ‘Two Hundred Thousand Silver Coins'; it was the same play produced under different titles. And ‘The God of Vengeance', a play by Sholem Asch.

Michael Greiber, writing in the 1957 edition of the Kovel Yizkor book, recalled of town life," . I never saw a Jew of Kovel raise a hand against another Jew. In spite of that, I was an eyewitness at a very early age to how the Jews of Kovel defended one another with no distinctions, in a case of suspicion of an injury done by a goy."

It was enough that a Jewish child of about 7 years old would burst into a home or shop, shouting: “I saw a goy chasing after a Jew” and immediately, in the blink of an eye, a group of dozens of Jewish youths would gather to judge the goy who would dare to attack Jews. I saw a young Jew, about 17 years old, a shop assistant (if my memory serves me, his name was Sushnaski, son of the Jew Izboyzchik) who attacked a group of Russian soldiers with a corporal at their head, for insulting a Jewish woman who sold pottery in the marketplace, threatening to treat her as if they were in Kishinev. That corporal was taken to the hospital smashed to pieces. His friends nursed their injuries for a long time, and only through the intervention of many goyim.

Political Stirrings

The late 19th and the early 20th century saw stirrings of political and intellectual activity. Hovevi' Zion, a group formed to further Jewish settlement in Eretz Israel, became active. Later, sometime after 1925 when he founded the Union of Zionists Revisionists, Vladimir (Ze'ev) Jabotinsky visited Kovel where undated photos of him in the Yad Vashem photo archive show him at a "festive dinner in his honor" surrounded around a big table by about 50 Kovliners, and then on stage speaking at a Revisionists meeting. Jabotinsky's group had broken away from the Zionist Organization because he advocated a much more aggressive strategy aimed at the immediate declaration of a Jewish state.

Friedman recalled Jabotinsky's visit in her interview with Centropa.org in 2004.

At the beginning of the 1930s, a rally was held inside one of the cinemas – it was either ‘Odeon' or ‘Ekspres', since there were two movie houses in Kovel – at which Jabotinsky spoke. I was there. Jabotinsky was an excellent speaker. I remember that he was a man endowed with great oratorical talent. I aspired to become an orator and envied him. Jabotinsky encouraged his audience to go to Palestine; the rally took place probably after 1933, after Hitler's rise to power, and Jabotinsky talked about the danger that might befall the Jews. The Polish government was very accommodating to the Jabotinskites...

Zionist youth movements sprung up, such as Hashomer Hatz'air, which stressed the need to leave the merchant class and become workers and farmer chalutzim (pioneers) in Israel. A group that was centered in Kovel was the Hashomer Trumpeldor, named after Josef Trumpeldor, a soldier and early pioneer in Eretz Israel who had become a symbol of Jewish self-defence in Israel.

But there were also organizations more intent on improving conditions in the lands where Jews lived. One that had a presence in Kovel was the Der Algemeyner Yidisher Arbeter Bund, or General Union of Jewish Workers in Lithuania, Poland and Russia, founded in 1897. Its focus was the new class of workers who were laboring in sweatshops and workshops with poor conditions, rather than those still living the traditional peasant life. The Bund organized strikes and demonstrations among workers in 1905-06. The Bund included not only workers, but members of the young Jewish intelligentsia who were attracted to Marxism and Socialism. It strongly opposed Zionism because its focus was to improve life in Russian lands and saw immigration to Israel as escapism.

Abraham Zapruder, who would become famous for shooting the 26 second film of the assassination of John F. Kennedy in Dallas in 1963, was born in Kovel in 1905. He had four years of Hebrew education and later left for New York in 1920 when the region was swept up by the Bolshevik-Polish war. In the book "November 22, 1963," author Adam Braver wrote that while still in Kovel, Zapruder "was watching his neighbors and fellow Jews being terrorized and slaughtered during the Russian civil war. The Zapruder family escaped because the fight would be futile; an escape that he remembers as both cowardly and brave."

World War I

The outbreak of World War I in 1914, pitting the Russian empire and ultimately its western European allies and the U.S. against the Central Powers (Germany, the Austro-Hungarian Empire and the Ottoman Empire), opened a six-year period in which Kovel twice found itself a focus of battle, first in the Great War and then in 1919-20, the Bolshevik-Polish war. Jews suffered cruelly in both, and during the years the city was back under Polish rule.

One visitor to Kovel during late 1914 and 1915 was the famous ethnographer Shloyme Zanvl Rappoport, better known under his pen name S. Anski, who was asked to organize relief for Jews caught in Russian Poland, Russia and Galicia between the warring armies of Russia, Germany and the Austrian empire. Poles, driven by anti-Semitism and their economic competition with the Jews, often would accuse Jews of being traitors to Russia and befriending and spying for the Austrians and Germans, and these slanders gained currency in the Russian army.

Cossack troops among the Russians were particularly brutal and would be so again in the Bolshevik-Polish war.What Anski found throughout the Pale (recounted in his book The Enemy at His Pleasure: A Journey Through the Jewish Pale of Settlement During World War I), were convoys of refugees, towns looted and burned to the ground and villagers taken hostage and raped. He wrote also of the Russian army's deliberate destruction of Jewish communities. He was in Kovel several times because, as rail town, Kovel was a central point in the movement of Jews left homeless in the region.

The chairman of the local Jewish committee, a Dr. Faynshaytn, told Anski that food was being confiscated in the stores by the Russians, bread was scarce and there was no sugar. An appeal to the Russian commandant to allow several boxcars of sugar to come in brought the retort, "Let the Jews put salt in their tea."

Residents of Kovel itself suffered not only severe food shortages but epidemics, and some were subjected to forced labor.

The battleground came to be known as the "Kovel pit" and the the Pripet Marshes north and east of the city were a key element in the fighting. The rail line from Kovel to Brest-Litovsk ran through the marshes which, for most of the year, are otherwise virtually impassable to major military forces. The few roads were narrow and mostly unimproved. So this geography influenced strategic planning of all military operations in the region.

"The railroad from Kovel to Lemberg, via Vladimir-Volynski, was built by the Russians during the war in 1914. We knew at the time that such a railroad was coming into existence, and marked it in our maps, and were quite happy to find it there, too, when a year ago I drove the Russians back with my army. This railroad was naturally further built out by us for our nachschub (procurement and supply of military materiel). ..The Kovel-Lutsk line is also good to have."

Kovel was the objective of a Russian assault launched June 4, 1916 known as the Brusilov Offensive after General Aleksey Brusilov who conceived it. Supplied by the Tsar with a large store of artillery and shells, Brusilov launched a battering ram attack, beginning with intensive artillery barrages followed by waves of advancing soldiers. Brusilov had the advantage of numbers over the Central Power troops defending Kovel, with 250,000 men to 115,000.

In a July 11 cable, the correspondent for the New York Times reported the Russians proceeding along the slow-moving and shallow Stokhod River from the Kovel-Sarny rail line towards the Kovel- Rovno main road. On a day that was "terribly hot, with a scorching sun…The Russians showed themselves utterly indifferent to losses or German shells, and at one point they forced a crossing of the Stokhod in face of the concentrated fire of eight German batteries."

In the book, "Rasputin: The Saint Who Sinned," about the "mad monk" Grigori Yefimovich Rasputin who came to influence the court of Tsar Nicholas II, the writer Brian Moynahan described the fighting this way:

In the fall offensive of 1916, at Kovel on the central front, a Guards army of the Semyonovsky and Preobrazhensky regiments attacked across open, marshy country seventeen times in three months...The guardsmen were sent into a swamp. German aircraft strafed them as they struggled in the mud, then refueled and rearmed, and returned to feast on the bottle green mass. "The wounded sank slowly in the marsh, and it was impossible to send them help," according to a history cited by Moynahan. "The Russian Command for some unknown reason seems always to choose a bog to drown in." In less than a fortnight four out of five of the empire's finest troops were lost. Half-trained reinforcements were ordered to continue the assault. They advanced in long, thin lines, dressing to the left, officers at the head, sergeant majors behind to shoot deserters. They made no attempt to maneuver; their officers did not think them capable of it. So many corpses lay in no-man's-land that the Germans refused a truce to bury them. Despite a terrible stench of putrefaction, the heaps were a physical obstacle to fresh Russian assaults. By the time the offensive was called off in November, the Russians were bombarding their own jump-off trenches to force their men into the attack. The bodies were swallowed slowly in the quicksands. Months later an officer posted there, Prince Obolensky, found that "still above the sand one could see the tops of their bayonets."

The New York Times on Sept.11 quoted Warsaw newspapers saying that Rozwadowski acknowledged "various sources of complaints referring to bad treatment by our troops in localities retaken from the enemy."

"Though it is a fact that part of the Jewish population during the time of the Bolshevist invasion has been hostile against our State and has supported the enemy, we cannot consider as guilty all Jews, some of whom, especially the Orthodox, were even patriotic," he said. "The command of all the armies will immediately take steps in order to stop all excesses toward the Jewish population. It is expressly forbidden to attempt mass revenge for the guilt of an individual, and if it happens, then the guilty must be tried."

Yaroslav J. Chyz, whose papers are collected at Harvard University's Ukrainian Research Institute, was a lieutenant in the radio-intelligence corps of the Austrian Army stationed at Kovel from March 1917 to March 1918. He recorded telegrams, nearly all Russian in origin, mostly from Bolshevik and anti-Bolshevik groups. Harvard's summary of the collection says "Among the telegrams, there are messages referring to Tsar Nicholas's attempt to escape, Poland's declaration of independence, Germany's peace proposals to the Russians, Aleksandr Kerenskii's negotiations with the Central Rada in Ukraine, the Bolshevik Revolution and to the Third Universal of the Central Rada" which proclaimed the Ukrainian National Republic in November 1917 after the Bolsheviks seized power in Russia.

The Russian losses in the battle of Kovel effectively ended Russia's role in the war.

The Soviets Invade Poland

In 1918, Poland emerged again as an independent state. But Russian leader Vladimir Lenin saw Poland as the gateway to spread the Bolshevik revolution to the industrial proletariat of German and launched the Russo-Polish War of 1919-20.

The larger Polish force became locked in an artillery engagement with three armored trains manned by the Soviets and while the Russian artillery inflicted damage on the Polish motorized unit, the batteries of the main Polish force severely damaged one of the armored trains which barely made it back to Kovel. The other two trains had to retreat to the west. An advance Polish guard captured the city's railway station, and the sudden appearance in the city of the motorized unit, firing in all directions, caused two of the divisions of the Soviet 12th army to retreat in disarray. The main Polish force arrived in the city at 4 pm.

The Russian Jewish writer Isaac Babel, who had fought on the Bolshevik side in the Russian civil war, wrote about the Soviet defeat in a semi-fictional book of stories and in his 1920 Diary.

"Two days ago," the narrator tells a friend, "the regiments of the (Bolshevik's) 12th Army opened the front at Kovel. The (Polish) victors' haughty cannonade thundered through the town. Our troops were shaken and thrown into disarray. The … train crept along the dead spine of the fields. The typhoid-ridden muzhik horde rolled the gigantic ball of rampant soldier death before it. The horde scampered onto the steps of our train and fell off again, beaten back by rifle butts."

Later, when the train has made its way out of danger, the narrator recognizes Ilya who, in the skirmish, "had lost his trousers, his back snapped in two by the weight of his soldier's rucksack." Babel's protagonist tells Ilya of a day four months earlier when he had dinner at the house of Ilya's father the rabbi, noting, "but back then, Bratslavsky, you were not in the Party."

"I was in the party then," the young man answered, scratching his chest and twisting in his fever. "But I couldn't leave my mother behind.""What about now, Ilya?"

"My mother is just an episode of the Revolution," he whispered, his voice becoming fainter. "Then my letter came up, the letter 'B," and the organization sent me off to the front …"

"So you ended up in Kovel?"

"I ended up in Kovel!" he shouted in despair. "The damn kulaks opened the front. I took over a mixed regiment, but it was too late. I didn't have any artillery."

…He died, the last prince, amid poems, phylacteries, and foot bindings. We buried him at a desolate train station. And I, who can barely harness the storms of fantasy raging through my ancient body, I received my brother's last breath."

Babel was in Kovel on Sept. 11, the day before the Polish assault. He says of Kovel in his 1920 Diary:

"The town has kept traces of European-Jewish culture. They won't accept Soviet money, a glass of coffee without sugar: fifty rubles. A disgusting meal at the train station: 600 rubles…I visit Yakovlev (a political commissar), quiet little houses, meadows, Jewish alleys, a quiet hearty life, Jewish girls, youths, old men at the synagogues, perhaps wigs. Soviet power does not seem to have ruffled the surface, these quarters are across the bridge…All day I look for food.""The life of the Jews, crowds in the streets, the main street is Lutskaya Street, I walk around on my shattered feet, I drink an incredible amount of tea and coffee. Ice cream: 500 rubles. They have no shame. Sabbath, all the stores are closed. Medicine: five rubles. "

The Red Army fell to defeat, advancing at one point to the gates of Warsaw in August 1920, but was then outflanked by Polish forces and forced to beat a disorganized retreat, suffering high casualties. The Soviets had to sue for an armistice.

But the aftermath of the war produced what the journalist Coningsby Dawson described as a panorama of "eloquent misery" as he travelled from Brzesc (Brest) to Kovel in January on a six week tour on which he had been sent by Herbert Hoover to report on relief work. (The future president was then head of the American Relief Mission to Europe).

In Kovel, which Dawson described as "a wretched hovel of a town," he met with Cristine Zduleczna of the Grey Samaritans, a group of bilingual Polish-Americans who came to Europe to help in the relief work. Dawson said of them, "All of them can talk the Polish language, and most of them are old enough to remember the land of their birth at the time when they emigrated. Because of their dual nationality they are invaluable as liaisons between the need of the country and the American authorities."

Dawson was appalled by what he saw in Kovel:

Kovel is a wretched hovel of a town, unsanitary, permanently splashed with mud, inhabited by Jews and White Russians. Nothing that Gorki or Tolstoir has described is more accursed and G-d-forsaken. Dirty, starveling shops, whose entire contents could be purchased for a dollar, stare out on a street which is a continuous puddle full of hidden holes and bumps. Droschkies, drawn by feeble ponies, move weakly through the squalor. No one seems to have anything to do. Men in mangy fur-coats with sweeping beards and unspeakably filthy faces shuffle aimlessly along the pavements. Soldiers step more briskly but with an expression in their eyes of people who are condemned. It was here, outside a dingy stable, facetiously named the Bellevue Hotel that we met Christine Zduleczna.

Kovel Returns to Polish Rule

The Treaty of Riga signed March 18, 1921 ended the war. West Volhynia was returned to Poland, but the rest passed to Ukraine. The treaty was signed in on 18 March 1921, between Poland on one side and Soviet Russia and Soviet Ukraine on the other.

Yad Vashem's Encyclopedia of the Ghettos During the Holocaust says that during these years between the two World Wars, Kovel's Jews were merchants, artisans and manufacturers. They shipped cattle and crops all over Poland, and owned sawmills, flour mills and factories.

The community suffered at the hands of the Poles. The American Jewish Yearbook for 1920 reported that in November, groups of soldiers renewed attacks on Jewish passengers in the railway stationand in adjoining streets. "Many beaten, and beards cut," it said. In 1921, the Yearbook boted that on June 3 soldiers plundered Jewish shops and homes. Later that month, they entered a synagogue during services, beat worshippers and mutilated a sefer Torah. On June 21, 200 Polish soldiers surrounded the Great Synagogue and cut and tore the beards of worshippers. Many were beaten and some tried to escape by jumping from the windows.

The writer Lewis Browne painted a mixed picture of Kovel on a visit in 1926, describing a city full of squalor and poverty that contrasted with "a wondrous spiritual intensity" of intellectual life. Writing in the now-defunct American Hebrew, Browne set this scene:

A main street - Ulica Warszawska - long, crooked, and as uneven as the dry bed of a mountain torrent, with huge black puddles through which ragged rickety children drag terrified cats by their tails. On both sides sprawl dilapidated one-story shacks and shops, some of badly-pointed brick, more of warped wood, and many of white-washed stone. Here in a dark cavern a short-sighted tailor tried to thread a needle while his seven squalling brats and slovenly fat wife struggle over a pot of stewed carrots. There in a basement a half-starved cobbler with a mutilated hand patches ancient boots, while his white-faced son in a corner pores over a Hebrew textbook on geometry. Here in a shabbily grander shop a fat little man in a skull cap sells crimson shawls to barefoot peasant women while his daughter with bobbed hair, rouged lips and glass-bead earrings reads Elinor Glyn in Polish. (Elinor Glyn was a British novelist who wrote romances, often with sexually charged scenes). There on a corner three long-bearded, long-coated men haggle over a loan of a hundred zlotis (ten dollars) at 80 percent interest ... Noise ... loud cries in Yiddish and peasant Polish ... people running to and fro, buying, selling, buying, selling ... the sound of boys sing-songing thier Hebrew prayers in some subterranean cheder, and of a gramaphone in a bar-room blaring "Yes, We Have No Bananas" ... A cow wonders disconsolately from its pasture; wet hens prink around in search of seeds among the cobblestones; an ancient Studebaker taxi without fenders swings madly from side to side of the road, rattling like a thousand camions; broken-down droshkies (open horse-drawn carriages) stand idle in the gutters ...

The place literally swarms with unhappy folk who once lived in tolerable comfort and dignity, but who are now reduced literally to destitution. And when one knows that a whole family can keep body and soul together for as little as fifty dollars a year here, one begins to realize just how destitute these starving folk are. I was shocked in Warsaw when I learned that the students in the Lubavitcher Yeshivah were given only one zloty - eleven cents - wherewith to buy a day's food; but one zloty in Kovel is reckoned almost a generous stipend. I am not exagerrating when I say that there are grown men and women, crippled men and sick women, who are subsisting in foul cellars, outhouses and kennel-like dugouts here on as little as five cents, even three cents a day.

In the face of that, Browne marvels that "the miracle is not so much that life is preserved as that it is preserved with a wondrous spiritual intensity."

People don't merely vegetate; they read and learn and think and dream. I am utterly amazed at the awareness of these people to what is going on in the world. Stand on any street-corner here, or in any little grocery or barber shop, and you will hear heated and strangely well-informed discussion of Pilsudski's policy, Trotsky's flight, Zangwill's death, Coolidge's silence, or Lord Birkenhead's verbosity.

Browne also records the generational changes taking place with youths wearing European clothes and not the kaftans and skull caps of the Pale and girls wearing short skirts, bobbing their hair and insisting on the right to choose their husbands for themselves. The old Orthodox discipline "has largely fallen into desuetude" among the young and even the middle-aged, writes Browne.

...The old can only stand aghast and bewilderingly wonder what has happened to their world. They cannot believe it was merely the war that caused this terrifying revolution ... Rather, they blame it all on Zionism. That which the ill-informed in America imagine to be a movement back to medieval Judaism is to the ill-informed in Poland a movement away from all Judaism. To the greybeards Weizmann is the personficiation of all evil, and Zionism is the most unspeakable of heresies. When an old Jew here wants to hurl his worst epithet at a rebellious son, he cries, "You -- you Zionist!"

From 1927 through 1939, three publications appeared in Kovel: Koveler Stimme [Kovel Voice]; from September 1936 Unzer Leben [Our Life] and Koveler Vochenblatt [Kovel Weekly].

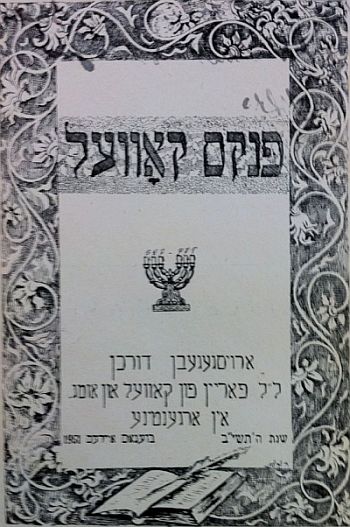

The Pinkes Kovel

Another feel for Jewish life in Kovel comes from a chapter in the Pinkes Kovel. Although the chapter does not identify the time period in which the story takes place, the introduction to the book itself says "the idea behind publishing The Kovel Book was born at the end of the WWII battles, after the defeat of Hitler when it was clear that the end of Jews in Kovel had ceased...[In it] we recreated and resurrected the glory and beauty which reflected our home city of birth. We did not scrimp, but rather did everything in our power to utilize the material at hand to memorialize the city." The chapter titled "What is a Pinkes? is a remembrance told by a Leybl Shiter about his effort to understand the meaning of such a record and his father's determination to become trustee of Kovel's "Society of the Concerned," a burial society, and thus the keeper of the book.

The elder Shiter found a way to get what he wanted because the man nominated for trustee, on Simchat Torah when that choice was made, was a Reb Shimen Zokner, who, being the owner of a tannery and a mill, had no time to fulfill the duties. It was quietly arranged that Shiter would take over the actual responsibilities.

So, on Simchas Torah, Leybl Shiter told a B. Baler, who recorded the story, Reb Zokner "was led from the study house to his home with great fanfare, where the crowd drank hot whiskey with honey and ate dumplings also fried with honey, and everyone had a wonderful time...The whole town knew my father was the real head of the society. It was as though my father were Shimen's secretary - no one complained about it."

Leybl's father put the Pinkes in a safe place in his store where Leybl took the opportunity to look at it when no one was around. He described it as a "large, old book, the size of a volume of the Talmud, with ribbed, leather covers torn in the corners. Out of them peeked the tops of yellowed, inscribed pieces of paper."

In awe, and some fear, Leybl tried to ask parents and family what a pinkes was, and what it meant, but they did not want to be bothered with his questions. He describes how he nervously approached his normally grouchy teacher, Reb Artshe Karliner, and buttered him up first by offering to fix him a hot glass of tea, which was one of the Reb's pleasures.

"After emitting a loud 'Aaaaaah' after each sip," Reb Karliner "answered me with measured words in his Lithuanian dialect:"

A pinkes, Leybele, is a book in which all of the unusual events and occurrences that take place in a town are recorded, both good things and, G-d forbid, not such good things. The good things are recorded, so that the generations that follow us will learn to behave well and will also perform good deeds. The bad things that happen, may we be spared, are recorded so that people may know not to do them, and also so that the One Abovewill pity us and see that no evil harms us in the future. Amen.

The work of putting together and publishing the Pinkes was overseen by editor-in-chief Eliezer Launi-Tzuperpin. The introduction says, "He energized the writers, invested his literary talents and experience, spent night and day collecting material and prepared the book for printing. He met with survivors, transcribed their testimony, gave it a Hebrew flavor, polished the material and arranged the contents."

In 1937, the Jewish population of Kovel was 13,200.

Kovel and the Holocaust

On August 24, 1939, the Soviet Union signed a "treaty of non-aggression," otherwise known as the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact after the the Russian and German foreign ministers, which pledged neutrality if either were attacked by a third party and promised not to join any alliances aimed at the other.

This immediately opened the door for the Germans to invade and occupy western Poland on Sept. 1. On Sept. 13, 1939, the Soviet Union pushed across the Polish border from the east and to "liberate our Ukrainian and Belorussian brethren from their enslavement to the corrupt, degenerate government of Poland" and, by November, had proceeded to annex the territory. The Polish Army collapsed.

The Red Army was welcomed in Volhynia, including Kovel where the Communist party was stronger than in other areas. "Kovel was the site of an enthusiastic welcome as Jews threw flowers at Russian soldiers, who for their part, just wanted into Jewish shops," according to "The Shoah in the Ukraine."

While the Nazis set out on their massacres of Polish and Jewish civilians, the Soviets in their territory granted citizenship to former Polish citizens who resided in western Ukraine and Belarus at the beginning of the month.

While this resolved the legal status of residents, it did not little to help with the hundreds of thousands of Jewish refugees because eastern Poland lacked the economic capacity to absorb them as they flooded Kovel and other cities. The American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee, founded in 1914 to aid Jewish populations of Eastern Europe and the Near East during World War I, was able to offer some aid in Kovel.

In the book "Isaac's Army: A Story of Courage and Survival in Nazi-Occupied Poland", author Matthew Brzezinski wrote that Kovel "had had a prewar population of 33,000 and was half Jewish. It had swollen remarkably...more than doubling in size with the influx of so many refugees."

"There was no unit for us to go to. We were directed east. I walked with a group of friends from the army in a crowd of people who were escaping from the Germans. In their haste people took with them whatever they had been able to lay their hands on. Then they realized that they didn't have the strength to carry it, so they abandoned various things including clothes and shoes – heaps of them lay in ditches.

The Soviet occupation effectively put an end to Jewish public and commercial life. Factories were nationalized, private commerce all but ended and craftsmen were forced to organize into cooperatives. Remaining were the Jewish high school, elementary schools and four kindergartens where instruction was in Yiddish and teachers tried to help their students hold on to the Jewish character.

Bob Golan, who with his family were among the refugees that ended up in Kovel, described Soviet administration of the city this way in his book, A Long Way Home, The Story of a Jewish Youth, 1939-1949 :

Our cousin's husband supplied cattle to the slaughter house and was involved in the distribution of meat so we had plenty of meat to eat while we stayed with them. But they also had their share of problems. In their effort to "communize" this newly-conquered territory, the Soviets revised the existing economic system in such a way that incentives were, lost, production suffered and there were shortages of many necessary goods. In general, conditions in the town were not much better than we had encountered in the Ukraine, and refugees were everywhere.

Mieczyslaw Weinryb told of his time in Kovel under the Soviets in his interview with Centropa.org:

...To my delight I found my family in Kovel. It turned out that when the war broke out my parents had bought a fairly big cart, loaded up some of the goods from the shop and their own luggage, of course, and gone east, to Aunt Lea. Margolia had gone with them because on the day the war broke out she was still in Zamosc, where she had been spending the summer holidays. In Kovel they lived from selling the goods from the shop. They were even able to rent an apartment.As for me, soon after I arrived in Kovel I saw a notice that they were looking for people to do construction work in a garrison left by the Poles that the Russians had taken over. I volunteered and was given the job. I was in charge of renovation work there. As a person employed in the Soviet garrison I was allocated a bachelor apartment by the municipal authorities. They billeted me in a private house. I remember that I paid the owner some rent. Thanks to the job in the garrison I was even able to help my parents a little because there was always the chance to take a bit of coal or firewood home.

When the Germans were approaching Kovel evacuation trains began to be put on at the station. People were going east in droves. I went to my parents and Margolia and tried to persuade them that we should all go together, but they didn't want to just drop everything immediately. They had no idea what might happen. My parents were older by then, and Margolia wanted to stay with them. They talked me into believing that nothing would be lost if they spent a few days packing and so on. I was younger. I sensed that something was going to happen. I decided to leave first, but I thought they would manage to leave in time and that we would meet up. Unfortunately they didn't make it.

Another account of life in Kovel before the Nazis arrived comes from Benjamin Mandelkern, whose family decided to flee to Kovel in September, 1939 when Russians troops pulled out of their town of Parczew. They headed for Kovel because "we were told it was a lot easier to find accomodation" than in Lutsk or other towns filling ip with refugees. They rented a large room on the outskirts of the city and slept on straw stuffed sacks. He recounted their stay in Kovel in his book Escape from the Nazis.

Life became harder by the hour. Basic food was harder to find and buy. No storekeeper or farmer wanted to take the Polish zlotys; they all asked for Russian rubles or for valuables like gold rings, watches, or diamonds. To get rubles the refugees found that they could sell their watches to the Russian soldiers, who were fascinated by western timepieces; the bigger the circumference of the watch, the higher the price they paid...The Russians were buying everything. They loved coloured scarves and ladies' colored nightgowns. Trade with the Russian army was the only way to get rubles to buy food.Rumour had it that some people had opened two freight cars at the train station and found them loaded with salt. Anyone could go and take as many bags as he could carry - this was wartime, and we had to survive as best we could. Four of us ran to the station, grabbed a 50-kilogram bag of salt each and carried them back to our room. It was a precious commodity: you could sell it for rubles or barter it for food with a storekeeper or farmer. We found more men and all ran back for more "gold." Too late. All the salt was gone. There were more closed-up freight cars on other side-tracks, but they were now guarded by armed Russian soldiers...

We had been in Kovel for five days. The heat wave of that September never let up. We were tired, exhausted from the heat, and even more from the news buzzing around us ...From what we could gather, the German army was destroying the last positions of the scattered Polish resistance. The German occupation of Poland was complete, except for Warsaw...

Still, the horror of what was to come may not have yet dawned on those in Kovel. The historian Tadeusz Piotrowski wrote in his book on the Holocaust in Poland that, at this point in time, "few in the eastern territories knew what was in store for the Jews except Hitler, who probably came up with the idea for the 'Final Solution' in September 1939 but did not issue his order for its implementation until June 1941." Piotrowski quotes an account by a refugee who fled the German occupation from Ostrow-Lubleski, also in September 1939, as saying, "Unfortunately, the Kovel Jews did not show any sympathy or hospitality for the refugees -- they were unable to understand or to believe what the Nazi murderers were capable of doing."

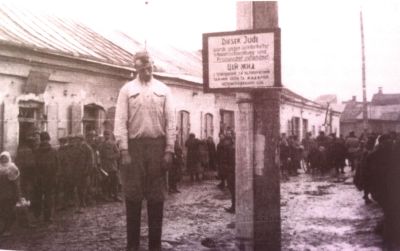

The Germans had always regarded the Molotov-Ribbentrop pact as tactical and temporary, and on June 27, 1941 they arrived in Kovel even as they were invading the Soviet Union. The Nazis arrived in Kovel on June 28, 1941 and immediately shot 60 to 80 members of the intelligentsia. The Enyclopedia Judaica said that, during the first month, 1,000 Jews were executed and 200 Torah scrolls, collected from all the synagogues, were burned. Water and electricity was shut off. A Judenrat was established, headed by a Wilik Pomeranz. Inhabitants had pulled down their homes at the orders of the Germans. Thousands of Jews were murdered in the nearby forest of Czerewacha by the end of the year. Two ghettos were established: one within the city for the disabled and the other in the suburb of Piaski. There were about 24,000 Jews in all in the ghettos, when refugees from neighboring towns and villages were included. The Germans separated the able-bodied, persons, from the elderly, sick and the children and marked the latter for immediate extermination. Jews were put to forced labor on a ration of four ounces of bread a day. The city ghetto was liquidated on July 22, 1942 and its residents were taken to nearby quarries and killed.

A Shmuel Pravda had this recollection of the Nazi occupation that he recounted in the Yizkor book of Kobrin:

Once, on July 7, 1941, I walked in the street of Kovel. A German stopped me. I had not taken my hat off as I was supposed to do. He saw the yellow star and he hit me with a whip. Blood spurted out. I was angry and depressed and went back home, packed up some food, took off the yellow star and started walking. My aim was Charnian, the region of Brisk. I had a knife to defend myself. I passed a village named Zameshin. I saw an old Christian coming towards me. I asked him where the Jews were and he said there weren't any more Jews. They had all been taken to the Brisk ghetto. When I told him that I was a Jew he told me to run because the Ukrainian militia was going to kill me.

Several groups operated in Kovel, according to the Pinkas Hakehillot Polin - Volyn Vepolesia: "Its members, who worked in the warehouse of captured Soviet armaments, stole weapons and even smuggled them to the forests. It seems that they had contact with the Soviet unit of Nasyekin who was a vehement anti-Semite. When the first group arrived their weapons were taken from them and they were murdered. In all likelihood this appears to have caused reluctance on the part of members of other groups and they remained in the ghetto where they perished at the time when the ghetto was liquidated."

But in the end, nearly all Jews of Kovel died. The process of liquidation lasted until October, 1942. During this time, about 1,000 Jews tried to escape but were rounded up and taken to the Great Synagogue before they were ultimately taken to meet their deaths.

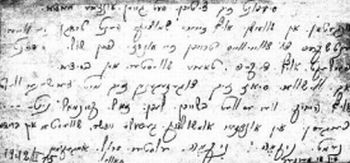

The Jews inside the synagogue filled the walls with wills and laments written in pencil or whatever other means they could find -- pleas that their loved ones be remembered and emotional cries for revenge.

In a note on the wall in Polish dated August 23, 1942, Tania Arbeiter wrote:

An account in the 1957 Kovel Yizkor book says that "the Nazis crowded all of the Jews of Kovel into the field of the city in order to kill them in the village of Bachba, 6 kilometers from the city along the Brisk road, in graves that had already been dug."

The book, "Kiddush Hashem: Jewish Religious and Cultural Life in Poland During the Holocaust," which explores the question of how the Jews found the spiritual power to endure their suffering, has an account of final words that Rabbi Twersky and the teacher, Joseph Avrekh, said to Kovel Jews facing their moment of execution. Described as a brocho for Kiddush Hashem, the act of voluntary self-sacrifice for the sake of an idea, Twersky is quoted as saying:

In a few minutes we will fall into this pit here and nobody will even know where we were buried and nobody will recite the Kaddish for us. And we so wish to live...Let us, however, united at this moment in a desire to sanctify the name of the Lord by renouncing even the Kaddish. Let us stand before the Germans in joy that we sanctified the name of the Lord.

The Jews are eternal. Our people will see your defeat, which is near. What a pity we won't be here to see it.

The Yizkor book chapter has this account of Avrekh (who had lost one hand in a childhood accident):

Yosef Avrekh rose up from among the rows of thousands of Jews being led to massacre, with courage and mental strength beyond one's comprehension, and raising his voice and his only hand, intrepidly - as was told by eyewitnesses - approaching the murderous Germans, he filled their ears with his wrath, spitting bile and contempt in their faces and predicting their inevitable defeat on the crucial day soon to come!

His single remaining hand was instantly amputated by the sword of the murderer. He was shot where he stood. He fell in battle. Wallowing in his own blood, he gave out one last battle cry: “The people of Israel live! Death and vengeance to the criminal Nazis!”

In his book Brisker Rav: The Life and Times of Maran HaGaon, Rabbi Shimon Yosef Meller quotes a survivor of the Brisk (Brest-Litovsk) ghetto, R. Asher Zisman, recalling that in Sept., 1942 "We've heard there are no Jews left in Kovel." He was told "my uncle R. Leib Lieberman was imprisoned along with many Jews in the shul before they were taken out to be killed. Jews drew their own blood and dipped their fingers in it to write down their names and their home towns. My uncle wrote on the wall of the shul in Kovel that he would soon be killed. He requested that the rav R. Ze'ev Soloveichik say Kaddish for him."

Zisman told of an acquaintance who met a businessman from Kovel where the Kovliner said conditions had been even more terrible than in Brisk. He said the commandant in Kovel was a "wild animal" who announced that it was a shame to have to waste bullets on Jews.

One Jew who did survive was 21 year-old Sophia Sarah Bronstein, according to an account on the Yad Vashem website. After the Nazi's first Aktion in 1942, Bronstein "fled to her apartment on Monopoliova Street, where she met her neighbor Elsa Kmitova. Elsa gave Sophia documents, and sent her with her mother-in-law Krolina Kmita and her husband Mikolaj to their farm in the adjacent village of Boza Drobka. The Kmitas covered Sophia’s eye, as though she were ill, and took her to their home in a cart, presenting her as a relative." Although some in Kmita's family wanted to evict her, Krolina refused and Bronstein hid with them until the liberation in 1944.

"We spent quite a lot of time in Kovel. That was actually my last stop in the army. And we lived a good life. We lived in the city itself. When we were not on duty, we were free to go wherever we wanted. I was in that famous synagogue. The Jewish Partisans took me in. I spent a lot of time with them. They were residents of Kovel. There was a Jewish doctor there, a Major. I was on guard duty. The commander called me and told me to escort the Major home, because he was short sighted. I led the Major. I also did not see very well, I did not have glasses … so he tells me, 'There's a pit here.' And we were inside the pit, and he was trying all that time to convince me: 'Roza, we are Jews, we can take pride in the fact that we are Jewish. The Russians, they are no better than we are. We as Jews need to be proud to be Jews. We are doing our part in serving our homeland.'"

After the War

A Sgt. S.N. Grutman, nationality unknown, who had worked in Kovel until 1940 as a headmaster of a Jewish school, visited Kovel in 1944 in search for his mother and mother-in-law and went to the huge two-story synagogue. He saw the burned Torah scrolls, the altar that had been pulled down and the pockmarks of automatic weapons fire.

Then, for him, "the walls began to speak" as he saw that they were covered in writing without a single empty spot. By one account, there about 95 notes.

"Leyb Sosna! Know that they killed all of us. Now I'm going with my wife and children out to die. Be well. Your brother Avrum, August 20.""August 20, 1942, Zelik, Tama, Jela Kozen perished. Avenge us!"

“Reuven Atlas, know that your wife Gina and your son Imush perished here. Our child wept bitterly. He did not want to die. Go to war and avenge the blood of your wife and your only son. We are dying although we did no wrong. Gina Atlas”.

"Nevinna krev zhidovska nekhai splyne na vshistskikh nemtsov. Pomsty! Pomsty! Nekhai ikh porun zabie. Kurva ikh mat." [Let innocent Jewish blood pour down on all Germans. Avenge us! Avenge us! May lightening strike them. Their mothers are whores. Srul Vaynshteyn, August 23, 1942)

Two young girls, signing only their first names, wrote that "one so wants to live, and they won't allow it. Revenge, revenge." An unsigned note was less personal: "For our innocent blood, for the tears of mothers and children. A tragedy such as the world has never seen, and dear D-d we will not be silent! We ask for revenge." A nearby line, with a simple surname and date, asserts that "God will avenge." Another young person tried to describe the experience of awaiting the end: "I write the last time before my death. If anyone should survive, may he remember the fate of our brethren. I am strangely calm, although it is hard to die at 20." A woman wrote her husband, so that "should he come to the shul" he would learned of the death of his wife and daughter. A mother and father asked for kaddish to be said for them, and for the holidays to be kept. A parent recorded that: "I die, innocent, with my little son." A girl wrote to her mother: "My beloved mama! There was no escape. They brought us here from outside the ghetto, and now we must die a terrible death. We are so sorry you are not with us. I cannot forgive myself this. We thank you, mama, for all of your devotion. We kiss you over and over."

The teacher from the Hebrew Gymnasium, Joseph Avrekh, said, "Murderers, our miserable blood will not keep silent. You will lose the war. There are enough Jews to revenge our blood. Woe to Jews who have forgotten how to take revenge. For the blood of their brothers and their faith. Revenge!"

As Grutman walked Kovel looking for remnants of neighborhoods he had known, he saw "not a trace of the houses remained; it was just like a wasteland, overrun with weeds as tall as a man."

Michal Friedman visited the city in 1944 after the Nazi occupation ended:

When I was returning from Russia on a troop train that passed through Kovel, I asked my commanding officer for leave of absence and went down to the town to look for the remains of our home ... I hadn't had any contact with home during that entire time. I had sent letters to my family from several localities, but I don't know if they arrived. And now I was on my way to Lublin. I walked through a ruined town; the house in which I used to live no longer existed.I found one acquaintance, a Jewish woman who had gone out of her mind. She was walking round talking nonsense. She had had a little child who had started crying terribly when they were hiding in some bunker; several dozen other people were hiding there as well, and they suffocated the child. Nine people survived from the entire town; out of 18,000 Jews. I came across a girlfriend of my sister's, a Pole; she gave me several photographs. She told me in detail how it had been done. I learnt about the torments the Jews had gone through, how they had been put behind barbed wire. During all that time, Marysia, that Polish girl, had been meeting with my sister in secret.

The Story of Bronya Wasserman-Eckhaus

The last breaths of Jewish life in Kovel were eloquently described by Bronya Wasserman-Eckhaus who wrote of reaching the city in the "Memorial Book of Ostrow-Lubelski, a town in eastern Poland from which she escaped the German occupation in September, 1939. She described the trip of 82 miles and her arrival:

The highways and roads were filled with refugees walking or riding in wagons. Carrying our few belongings in small packages, we finally arrived at the city of Kovel (a Jewish population of about 20,000), where we found a place together with many comrades from the socialist movements and some former political prisoners. In that house we were fed, very often we heard lectures, held meetings and discussions, but it was not permanent.

One early morning in June 1940 the Soviet army arrested all her husband Getzl, Misha's brother, and my youngest sister Tamara, all arrived in Kovel. My youngest sister Sarah remained in Ostrow with our parents. My sisters and brother-in-law tried to find a place in Kovel but it was not easy to find a decent place to live and work, and, like many refugees, they decided to register to go back to German-occupied Poland. Unfortunately, the Kovel Jews did not show any sympathy or hospitality for the refugees - they were unable to understand or to believe what the Nazi murderers were capablc of doing.

I obtained citizenship and started to work at the railroad station.

Misha and I decided to get married. It was a small ceremony, in the presence of some friends. My parents and my little sister Sarah and Misha's parents were in Ostrow. My two sisters and brother-in-law were in Siberia. Their letters were desperate ones; they suffered from cold end hunger. I remember how we started to send them parcels of food and clothing. We shared everything with them and they were very grateful.

In October 1940 I became pregnant. Through my working at the railroad station's bookkeeping department I made friends with many Polish railroad workers and also with a Jewish girl, Basha, who came every day to the office from Kamen-Kashirsk. We became very good friends.

At that time the political situation was not a very happy one. The news told about Germany's military victories in Western Europe. The world was dreaming, indifferent. But still, we believed in miracles. We were young and enthusiastic. At the end of March 1941 my husband, Misha, was called to military exercises for a few months. Actually, we could have arranged for him to stay home since I was pregnant and without any other relatives, but our views did not allow us even to consider this. We believed that it was our duty to be prepared to fight against the enemies - the Nazis.

Our separation was a very sad one. Misha was to return from his military service at the end of June 1941. I tried to manage the best I could. My friends at work were helpful, especially Basha. She often brought me tasty food. She looked after me. She was so good... From Ostrow-Lubelski to Kovel.

From Ostrow-Lubelski to Kovel.One Friday evening, June 19, 1941, my son was born in Kovel State Hospital. On Sunday, early in the morning, sounds of air bombardment aroused us. There was a turmoil, but soon high-ranking Soviet officers assured their wives and us that these were only aviation exercises. They were mistaken: it was the beginning of the war. German airplanes and bombs were making the noises. At the hospital there were many patients: sick people and women with newborn babies. Husbands and relatives came in a hurry to take them home. I asked myself constantly: "What to do? Where to go? To whom could I turn?"

My husband's parents and my sisters were far away. The house where I lived was closed because it was situated near the railroad station and that area had been heavily bombarded. What to do? On Tuesday morning my friends Henia and Fajvel Hammerman came to the hospital and took me and my child to their home, even enough they themselves lived in one small room. They told me that on Monday most of the Soviet citizens, officials, police and miltary personnel had fled Kovel but had returned on Tuesday morning. Howevel, no one knew what any moment or any hour would bring. My friends Henia and Fajvel were in the streets attempting to hear some news. On Wednesday evening they returned with the news that the Soviets were leaving again and that empty cars were waiting at the station to evacuate the people, to take everyone who wanted to go. On Thursday my friends left in a hurry. I, with my six-day old child, didn't feel the strength to go with them. I was too weak.

Kovel was occupied by the Germans. On June 29, 1941, hell broke loose... My landlords asked me when I would be Ieaving the room since they knew my marital situation and didn't want to have such a tenant... Where to go now? I don't know how, but I remembered the Silberman family, which I asked if I and my child could stay with them. Abraham Silberman, born in Lublin, and his wife Malka, born Kagan in Kovel, had three children: Marale, Sheivale and Menashele. They accepted us; they were very good and noble people. Malka's mother, her two married brothers, with their wives and children, sister, nieces and nephews, were friendly to me and I felt like part of the family.

Right after the first days of the occupation the Germans and their Ukrainian collaborators began their sadistic actions against the Jewish population. Every day, every night, there were different orders, arrest raids, groups of Jewish people killed. Abraham Silberman was one of the first victims. The Ukrainian police arrested him together with more well-known Jewish citizens and massacred them. They were forced to dig their own graves. I saw this, I was a witness. Malka, the unfortunate widow, the three little orphans, together with the whole family and I, mourned Abraham Silberman's death.

Notices appeared to volunteer for work but not one of those who went to the labor camps was ever seen again. We lived in continual fear. The names of Kassner and Manthel, the district commandants, were enough to frighten the Jewish population. I was watching when Mr. Motel Kagan, Malka's brother-in-law, was killed, shot together with some other strong young men. (I was a witness in Oldenburg in Germany in 1965, against the two Nazi murderers, Kassner and Manthel) ...

At first we were marked with arm-bands bearing a Star of David, later with yellow patches. Every Jewish house was marked. In the spring of 1941 two ghettoes were constructed--one in the old city around the old synagogue not far from the market, the second in the new city, not far from the railroad station. At first there was a free choice where to stay. but one morning before Shavuot an order of segregation came: people with work certificates should stay in the New City Ghetto; the others, the elderly, people with children, the sick, were to stay in the Old City Ghetto (without work certificates). By the afernoon everybody must be in his place. The whole day was a shocking chaos, turmoil--impossible to describe. People were running back and forth; families and friends were separated. Field outside Kovel where a Jewish massacre was said to have taken place. Courtesy of Lynne Siegel

Field outside Kovel where a Jewish massacre was said to have taken place. Courtesy of Lynne SiegelI and my child should have gone to the Old City Ghetto, but I decided to stay in the New City Ghetto and to wait for an inspection. I took the risk.

I remember well that day, the evening... The people around me... The night and the early next morning when the rumors came to the New City Ghetto that thousands of Jews had been shot and killed... dragged off in trucks from the market place to sand pits and thrown in, dead or half-dead, and covered with soil... Can we understand such things; that such murders can happen?... Rumours came from Polish people that the earth was shaking a long time afterwards. I and my child were supposed to be in those pits; we were saved by chance.

Now we remained alive and were ordered to go with our bundles to the Old City Ghetto. We were cramped together, thousands on thousands, the remnants of many previous selections, all humiliated and in a state of continuous danger. Together - the sick and the healthy.

There was a shortage of food and medicines. Everyone had one desire--to survive. To survive, to take revenge... Revenge!

The second ghetto had a short and tragic end. One day in July 1942 rumours came that Kassner and Manthel, the Nazi commanders, had appeared in the city, that the ghetto was surrounded. This was always an ominous sign. Everybody went into hiding in hiding places prepared in advance. We did not have any choice. Together with my child I hid in a shelter on the roof, together with the Silberman family, the Kagans and others... Twenty twenty-two people. The shelter was dark and small. We hid behind a wooden partition. We were cramped, thirsty, hungry, dirty... The few chamber pots were emptied downstairs at night. All the time we heard gunshots and screams, orders in German and Ukrainian. Days and nights passed in fear, cramped together, but still with the hope of surviving. Hope that after a few days the action would stop...

My child was hungry, dirty and wet. He was suckling. What did he have to suck from me? I hugged him, but he cried, and one afternoon we heard knocks on the wooden wall of our shelter and voices in Ukrainian: "Fellows, a child was crying here. We must get an axe to destroy the wall." They left and didn't come back; they were sure we could not run away.

There are no words to describe the tension in the sheler. I felt guilty. As night fcll I heard whispers: "You have to do something with the child. He can't stay here alive'... We must do everything to survive, to take nevenge'... Somerbody gave me a big scarf... I was holding the child and the scarf... I knew that my unfortunate frienns were right. The child was looking at me and I didn't know what was going on in my mind. The friends around me, the women, men, girls, boys, the darling children: Marale, Sheivale, Mcnashale, Esterl, Dvoshale-- they all loyal my child very much... They were all frightened... They suffering, the sadness in their eyes. I looked around and I whispered: no... no..., I am not going to kill my child... I am going down with the child. It was dark; very dark for all of us. Somebody prepared a ladder and I came down to the empty, plundered house with gaping doors, open windows, wrecked and robbed. Saying Kaddish at a mass grave. From the Pinkas Kovel

Saying Kaddish at a mass grave. From the Pinkas KovelI found a place to wash my child and to feed him. I even found some aspirin tablets to make him sleepy. Nobody came in... Outside there was shooting. I stayed in that open house for a few long days and long nights. There was less shooting, less screams, and I began to think that I should go out and that the aktzion was finished. I was mistaken. I left the house with my child in my arms. It was a hot day in July--summer in Poland.. I came to the high fence of the ghetto, not too far from the gate to the unfinished bridge, and I could hear orders in Cerman and Ukrainian: "Halt, halt, come here, come herel"

I remember that I was thinking that we were going to be killed. I came closer to the gate and a Ukrainian asked me: "Where are you going?" and I could hear my answer in Polish: "I came in and I don't know how to get out."

The only possibility was to have "fallen from the sky," but surely they all were drunk. I can hear the answer: "Go through the gate." I went through the gate. We were out! Out of the ghetto... A big free world, but not for us... a homeless woman with a child without a right to live...

Wasserman-Eckhaus was one of the small number of Jews who escaped the Nazi occupation of Kovel. When the Soviets recaptured the city in 1944, some, like S.N. Grutman and Michael Friedman, returned to see what was left. About 40 Jewish survivors returned over the following months, but they did not stay, leaving for Israel and other countries. The community was not re-established.

For, to our immense loss and sorrow, this Pinkas Kovel is the only remnant that remains of our beloved hometown. -Leybl Shiter as told to B. Baler

Copyright © 2009 Bruce Drake