Copyright © 2017 Martin Davis

The Early Jewish Community

Bălţi (Beltsy, Belz) originally came into existence as a small village, of which, it is said “In 1580, the locality later named Bălți was formed around a small Jewish tavern”1.with a chartered horse and cattle fair, from the Middle Ages. In 1469, a Crimean Tatar invasion led by the khan Meñli I Giray burned Bălţi i to the ground, before the invaders were defeated. The site was rebuilt slowly and it also became a centre of handicraft, with smiths, wheelwrights, leather dressers, saddlers, and cartwrights. For most of its history, up until the the 18th century, it was part of the Ottoman (Turkish) Empire. A Jewish community began to develop in Bălți in the middle of the eighteenth century. After their legal status was formally established in 1782, Jewish traders and manufacturers were invited to settle in the area in order to develop the region's economy and trade. At the beginning of the 19th century, Bessarabia was conquered by Russia, and the Russian authorities encouraged Jewish immigration to Bălţi, for the sake of the town's development. Bălţi held the most important horse and cattle fairs in the whole of Bessarabia. As a result, the city established a network of places to lodge, taverns, tea shops, restaurants and even workshops that served the fairs' visitors. As a result, the Russian-Turkish agreement signed in Bucharest on 25th May 1812 Bessarabia was annexed by Imperial Russia. At this time there were about five thousand Jewish families in Bessarabia and these included people from Podolia, Poland and Germany. A small portion were "Sephardim", descendants of Spanish Jews, according to the census in 1812 the imperial authorities in Bălţi identified a Jewish population of 244 families with a total number of 1220 people. The Jewish population grew due to the Russian policy of encouraging settlement in Bessarabia. Their numbers increased steadily—from 244 families in 1817 to 1,792 in 1847, rising to 4,365 in 1857. The Jews of Bălţi worked in a range of professions, from traditional Jewish occupations in trade and religious occupations, to those areas considered unusual for Jews – such as leather workers, saddle makers, seal manufacturers, soap makers, carpenters and builders. Many of the Jews in the town made their homes in the rural surroundings. Some leased or bought land, and laboured in agriculture. They grew wheat and worked in vineyards and orchards.Mid 19th Century - Rapid Development

In the second half of the 19th century, a hospital was established in the town with 15 beds. "The Association to Aid the Underprivileged Infirm" was supported by the wider public, as well as by philanthropists from the town and the "Providing for the Poor" association, which distributed food and wood to the needy population of the town. Later, other aid funds were established – "The Fund for Jewish Manufacturers" and "The Fund for Professional and Agricultural Training" – and even a restaurant for the poor. Bălţi was the largest sunflower-oil producing centre in Bessarabia, with many Jewish people working within the industry; the oil produced in the town was sold regionally and exported abroad. The energy station in the town was owned by the Jewish Rozentoler family. The Jews of the city also set up flour mills and factories manufacturing candy, food, alcohol and its derivatives, soap, candles and cotton wool. During this period a significant number of Jews from Austrian Galicia and Russian Podolia settled in the town. By 1894, the city had become a railway hub, connecting with Czernowitz, Hotin, Kishinev, Bender, Akkerman, and Izmail. The city was a regional centre for the collection of wheat and other crops, which were then transported by railway to Odessa. It also gradually developed into a centre of commerce in Bessarabia, primarily dealing with cattle. At the beginning of the 20th century, the town was an industrial city with a well-established commerce and many small factories. Towards the end of the 19th century, a Talmud Torah was set up in which 100 disadvantaged children studied. A local philanthropist (Halperin) donated a building from his estate to house the Talmud Torah (as well as one for the hospital, and one for a public bathhouse). Besides Jewish studies, the Talmud Torah taught Russian and mathematics, and later undertook vocational training. By the end of the 19th century, the Jewish school in the town began to prioritise secular education, with Torah studies integrated into the syllabus. However, the continued discrimination against the community by the Imperial Russian authorities, led to mass emigration from Bălți to other countries in Europe, the United States and to Palestine.1900 to 1939

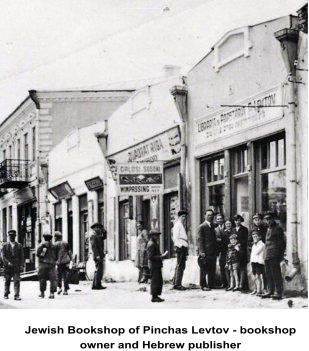

The town’s economy expanded in the first part of the 20th century, and the town/city started to diversify. The town was not directly affected by World War I, aside from the recruitment and movement of troops. At the outset of World War I, most men in the region between the ages of 18 and 45 were enrolled in the Russian army, and subsequently self-organized into Moldavian Soldiers' Committees. They became a political force which drove many of the subsequent changes. Many of the remaining older town buildings date from the inter-war period. References: 1. United States Commission for the Preservation of America’s Heritage Abroad 2010 - Report on Jewish Monuments in Moldova Yosef Mazor and Mishah Fuks, eds., Sefer Balti Basarabyah: Yad ve-zekher le-yahadut Baltsi (Tel Aviv, 1993). 2. This photo is reprinted from Jewish Roots in Ukraine and Moldova (by Miriam Weiner) with permission of the publisher, The Routes to Roots Foundation, Inc. http://www.yivoencyclopedia.org/article.aspx/Balti Encyclopaedia Judaica (1971): Beltsy, E. Schwarzfeld, Din istoria evreilor...in Moldova (1914) M. Carp, Carta Neagra, 3 (1947) Feldman, in Sefer Yahadut Besarabyah. Yuri Rashkovan, My Balti (unpublished)

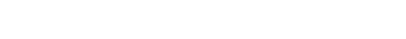

Former Jewish Cultural Centre in 1993 - the building is now the

Dnestrovskii Institute of Economics and Law

Photo credit: Miriam Weiner Archives2

The Bălţi (Belz) Old Synagogue complex - circa 1910

In 1861, Bălți had 8 synagogues; by 1910 there were 14. Yisra’el

Joffe served as a rabbi from 1885. A network of Jewish institutions

existed in 1930, including a teachers’ seminary, three elementary

schools, two secondary schools, a school of commerce, a

professional school for girls, a hospital, a home for the elderly, a

cooperative credit bank, and libraries.

At this time, Jewish state schools also began to operate in Bălţi, at

the initiative of the Russian authorities that endeavoured to

integrate the Jews into the general population. As a result, new

educational ideas began to spread among the members of the

Bălţi Jewish community.

At the end of the 1860s, some Jewish children were attending the

regular (non-Jewish) schools, and many of them were sent to

private tutors to learn Russian, German and Mathematics.

After May 1882, Russian laws prohibiting Jews to live in villages

were rescinded, and by 1897 the number of Jews in Bălți had

increased to 10,348 (56% of the population).

The most influential trend in the city’s Jewish community, was Chasidism. At the head of the

Chasidic Chabad centre before the First World War were the major scholars of the Torah, Chaim

Bar-On and Noah Sofer. The official (State approved) rabbi of the time was Rabbi Shimon

Yakubofa.

By 1930, Bălți’s 14,259 Jews constituted the majority (60%) of the town’s population. Their

primary occupations were in commerce and handicrafts; some suburban dwellers also had

farms. In 1925, of 1,539 members of Jewish cooperative credit banks, 656 were engaged in

commerce, 441 in handicrafts, and 156 in agriculture. Anti-Semitism was rampant at the time,

with pogroms and desecrations of the Jewish cemetery occasionally taking place. A major

pogrom occurred on 15 June 1930.

Yet, during this period, there appeared to be signs of a more positive attitude toward the Jewish

community and there was something of a Jewish cultural renaissance. In 1929 and 1933, Jews

were elected as deputy mayors of the town. Also, Shurot, a Hebrew literary magazine, was

issued in the town between 1935 and 1938. In the mid-30s Jewish community leaders

successfully provided public organizations; such as a hospital, a shelter for establishing

relationships, elementary, industrial and male and female high schools, a public kosher dining

room, a medical centre, public library, a kindergarten, a night shelter for the homeless.