| The history

of the Jewish community in Zeimelis, lacked attention by historians. There

are no books or articles about this community, which consisted of 679 people,

100 years ago. Large military engagements during the world wars occurred

far away from Zeimelis. Most of the Jewish houses, including the wooden,

are still there. But there are no Jewish owners. All information in this

article, I gathered from different editions, from archival documents, and

from meetings with people who lived in Zeimelis. I chose Zeimelis because

it is my father's and grandfather's homeland.

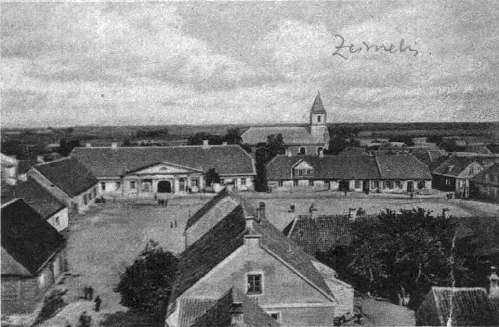

Zeimelis, previously called Zeimeli until 1917, is a small town in northern Lithuania, close to the border with Latvia. Here in the Zemaitia region, Lithuanian tribes have been living for hundreds of years. Liven Crusaders conquered those lands which now comprise the Baltic region. By the end of the 13th century Crusaders conquered Zemaitia. In the 15th century Zeimeli was a shopping center of local importance. It was on the cross roads between Kaunas and Riga, and Sidabre and Plonenai. The Liven Order broke apart in 1561. The adjacent lands of the Liven Order, referred to as Kurland, became a duchy. It became a vassal state of the Polish king. The borders between Poland and Lithuania changed many times and in 1585 the border passed right through Zeimeli. In 1586 Zeimeli was called a shtetl (small village). Since 1587 Zeimeli has been part of Lithuania. It was a crime for Crusaders to give shelter to Jews. That is why there is no mention about Jews during this period. The first mention of Jews in Zeimeli, was in 1593. Yuda , who was a member of the Jewish community of Troki (Trakai), a small town in Lithuania, lived in Zeimeli. This Yuda and several other people pleaded for Shimon Yakhimovich, who was arrested. Shimon was the brother of Ivashka Yakhimovich. This Yuda was most likely a border guard clerk, because Zeimeli was right on the border. The king sold the rights of doing the customs work on the border mostly to Jews, who prepaid the king in advance for this privilege. In the 17th century the first Jewish communities were established nearby Zeimeli. In the second quarter of the century, Jewish communities were established in Birze (Birzai), and in the 3rd quarter of the century in Posvol (Pasvalys) and Salaty (Salociai). The first items of information mentioning the existence of a Jewish community in Zeimeli, was in the middle of the 18th century. According to the census in 1766, 428 Jews lived in Zeimeli. The next mention about a Jewish community, was during a rebellion with Kostiushko as the leader. The Russian army fought against rebels in Kurland which was a part of Lithuania. In 1794 the lieutenant colonel of the Russian army Shults reported: “I just received news from the Jew Solomon, that in Seimen (Zeimel), which is a half a mile from the border, that they got an order from Vilna to collect double taxes from the Jews.” The Russian general Repnin testified: “Because of these circumstances, the Lithuanian Jews did not side with the rebellion, and helped fight against it.” Since 1795, Zeimelis has been part of Russia. We found archival documents about Zeimel’s kahal. The controllers found out after 8 auditings of the 1834 census lists that there were 6 Zeimel Jews whose names were not written down in the documents. We also found the box tax lists for Zeimeli for 1845-1852. From these lists we learn that during 1845-1847, there were 404 people registered, which was less than in 1766. The number of people who became poor during the year increased by 22, and the sum of the box tax for payment for them, was reduced 3 times. The reason - poor harvest years and exiling Jews out of villages. Then people paid even less tax than before. Communities became even more poorer. In 1851 prince Liven, the landowner, not pleased by his profit and income from the Jews, decided to exile Jews out of the village. He asked the Kovno guberniya government to approve his petition, claiming that he needed this land for his own use. The committee approved his petition. Because Jews in Zeimeli did not own any property and did not have any legal documents to prove that they lived on this land. The committee sent their decision to the Senate. From this we can assume that Jews, who lived there for a long time, did not own any property, and did not have any documents, to prove that they lived on this land, legally. The Senate did not approve the committee's decision. For a short period of time a temporary settlement was achieved. In 1856 prince Liven, again petitioned the committee, to evict Jews from Zeimeli. The Jews felt that they were in danger, and they asked the Senate to let them live on this land, and order the owner to let them build houses. The Jewish community promised to pay taxes from using the land, and asked the Senate to give the landlord some state land. In 1859 the Guberniya government decided “Jews in Zeimeli have their own community, religious school, cemetery, and they have the right to live there. Also breaking up this community will make it more difficult to collect taxes. The committee decided not to approve the petition and request of prince Liven.” The court's document that Jews could live on this land was 10 years old, so the synagogue was built no later than 1833. According to the census in 1897, the population in Zeimeli was 1266 people, from them 679 - Jews, 21 small shops, 2 restaurants, and as existed 200 years before, 7 cafes. Fairs were held 6 times a year, and trading days were weekly on Thursdays. From library

and archival sources, lets proceed to personal interviews, I had with various

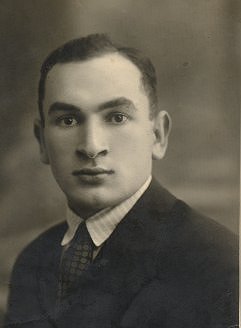

people who were born in Zeimelis. My main source of information is my father

who was born in Zeimeli in 1901, and Feivel Yosifovich Zagorskiy born in

Zeimeli in 1910.

Jewish houses stood on the grounds of prince Liven, and the Jewish community had to pay taxes regularly. According to my father, Zeimeli was not considered a town, but a village, and that is why Jews couldn't live there. They had to pay the local authorities every month. The chief of the local administration came regularly to my grandfather's house and drank several shots of Vodka, took a bribe, and didn't bother Jews. My grandfather woke up at 4 o'clock every morning and worked very hard. The family had 4 cows and several horses. My grandfather loved horses and could recognize a good one. Even prince Liven sometimes asked him to sell him a horse which he picked out. My grandfather bought a pony for his son. The family did not have a garden, but my grandfather rented 20-50 acres of land, and employed hard workers, who took care of this land. My grandfather bought the forest cut trees and sold them. He also bought wheat, rye and flax, and sold them in Riga. From Riga they were later shipped to England. He was a wealthy person in Zeimelis. Lithuanians borrowed money from him to buy land or houses. The interest rates on these loans was probably low, as people from Zeimelis remember him extending credit to them, with gratefulness. Ivan Atonovich Tauperis from the adjacent village remembers: “My father did not have enough money to buy a bicycle for me, which cost about 100 litas. He went to his neighbors, to borrow money. The neighbors replied “We are very poor, and besides you will not pay us back”. My father went to the Jews. Chayesh told him: “Take the money, I do not need to have a bill, guarantee or witness.” I got my bicycle. I am almost eighty, but I remember this episode.” In my grandfather's house there was a big textile store, approximately 15 square meters. My grandmother ran this store and she was a second rate merchant. My grandfather's sister and servant helped her. She had several types of fabric which she bought from wholesalers in Riga and Mitava in Latvia (now Elgava). She did not need to pay for the fabric until she sold it. People from villages willingly bought a lot of fabric. My grandfather was very religious, observed old traditions, did not allow himself to be photographed, and hoped that his son would become a Rabbi. There was a wooden synagogue near Bazaar square on Pasvalio street. The room for praying was rather large, between 60 and 80 square meters, with appropriate furniture. In the beginning of the 20th century a new extension was added to the synagogue. The Rabbi as head of the synagogue, managed the Talmud Torah religious school, and made sure that all boys could read and write. The teacher was an ordinary Melamed who knew nothing about secular subjects. He taught reading and writing in Hebrew, and translated the text into Yiddish. For classes, they rented a room in a private house. The Rabbi taught all students at the same time. Feivel Zagorski went to Kheder until he was 13 years old. The Rabbi and Gaba did not like government (secular) education. “Secular education is education without God in your heart”. Only wealthy people could afford secular education. In Zeimelis, lived Jews, Lithuanians, Latvians and Germans, but no Russians. My father spoke, Yiddish, Lithuanian, Latvian which were his three native languages, and a little German. He did not speak Russian. There were many estates belonging to German landlords around Zeimelis, and my grandfather conducted business with them. That is why he could speak German. He could sign his name in Russian. My grandmother was from a more educated family, so she could read in Russian. She wanted her children to have a good education, so she sent her daughter to a grammar school in Mitava in Latvia (now Elgava), and bought her a piano, on which she was taught to play. When, at the end of the 1900’s, two Latvian teachers opened a school in Zeimeli, my grandmother insisted to her husband, to transfer their son (my father) from Kheder to this new school. The only industries that were in Zeimelis were craftsmen, shoemakers, tailors, and bakers. People preferred to make their own bread. In my grandfather's house there was a big Russian oven. The owner of the bakery lived near the church. Children bought small bagels, and spread butter and honey on top. This was the only cake in Zeimelis. The tailor in Zeimelis was Zuskin, father of the famous actor Benjamin Zuskin from the Michael's theater. This tailor made school uniforms for my father in 1912. The emigration started long before W.W.I, when my father's grandmother emigrated to Palestine. Later my father's two uncles also emigrated to Palestine. Zagorski’s uncle left for America, when his mother became a widow, and helped her with money from there. During W.W.I in April 1915, great prince Nikolai Nikolaevich gave the order to resettle all Jews from all areas of war zones in Kovna Guberniya, including Zeimelis. After W.W.I some of the evicted Jews returned to Zeimelis, but not all. Zagorski’s family returned during August 1918, and my father's parents returned in 1920. German military units remained in Zeimelis until 1920. They built a railroad in Zeimelis. Relationships between the Germans and Zagorski’s family were very good. They lived in Zagorski’s house, and his mother, a widow, made bread for them. They always paid and respected her. Witwe- the widow must not be offended. During a land reform in capitalist Lithuania, German barons Hahn and Grothuss lost most of their lands. Jews went to Hahn’s mill because they made very good flour there. Grothuss had a huge garden. The crops from this garden were sold to Jews, who transported the crops via cart to the market in Siauliai, which they then sold. Zagorski knew all the stores and their owners on Bazaar Square. A lot of new stores opened in capitalist Lithuania and peasants shopped less often in Zeimelis. Many of the Jewish businesses became bankrupt. The Jews gradually left Zeimelis for larger cities and abroad. Their businesses were taken over by Lithuanians and Latvians. The Jewish community had it's own library. Zagorski remembers: “The first time I visited this library was in 1923. Yudel Rappaport and Abram Erlich founded the library. There were about 250 to 300 books in the library. It was located in the mezzanine of Ger’s house. In 1927 a new Jewish elementary school was built, and there was a room there for a library. People who were responsible for the library were: Leizer Milunski, Hirsh Kremer, Rappaport, Erlich and I.

There were usually 100 or more people in the audience. All money collected from these plays was used for the library. They purchased books in Kaunas. Once in a while they had meetings and decided what books to buy from a catalog. When everyone had read a particular book they exchanged it for another book. They exchanged books with other libraries in Vaskai and Linkuva. Similar libraries were in most towns.” Zagorski said: “In Zeimelis in 1929 there was a very famous criminal case. All of Lithuania talked about it. A new slaughter house was built and butchers slaughtered cattle there. To get permission, they invited a clerk from the lower court administration. The clerk arrived very late, checked everything, and went home. There was an old, unprotected well near the slaughter house. Everyone knew about it and did not go too close, as to not fall in. The clerk did not know about the well, and because of the darkness, fell in. When he did not come home on time, his wife became nervous and notified the police. They found a body in the well. The Jews were accused of deliberate murder. This case lasted for a long time. Among the customers were some Christians, as Jews cannot eat the meat from certain parts of the cow. One suspect, a Christian customer was a sickly man and not strong enough to kill this clerk. That is why they accused Jews, and sentenced them to 15 years in prison. After the court's decision, the Jewish community of Zeimelis raised some money to hire lawyers to appeal etc. They raised 15,000 litas. The case went to the second hearing. But the court decided that the Jews were guilty and sentenced them to 18 months in prison.” During 1932-1933 the teacher Zalman Volovich created a branch of the organization called HeChaluts. This organization prepared young people for agricultural work. After working and participating in agricultural work, participants were given a letter of recommendation, for them go and work in Palestine. So in 1936, Abramson, Abka Ger and Ester Kremer, left most probably for Palestine. There was a branch of the “Jewish National Fund (Keren Kayemet)” which raised money to buy land in Palestine. The last chairman of this fund was Abrom Shulheifer. He asked young people to raise money once per month. Most of the Jews were very poor and could only afford 5 or 10 cents every month. They also collected money, the same way for the Talmud Torah school. Zagorski attended this school at first, since he was from a poor family. There was a service to help sick people. People who came to spend the night with ill people. During the day, relatives took care of patients. This service organization did not have a leader, as it was an old custom, and it was not necessary to invent something new. Young people - Abe Ger, his sister who was a dentist, Ester Kremer and Feivel Zagorski decided that they would spend the night with a sick person. It didn't happen very often, and it wasn't very difficult. There was a “Khevra Kadishha”, a burial society. They shared a place for prayer, and a room where the Rabbi lived. At first there were 20 members, and in the final years only 5 or 6 members. They took care of the dead person and prayers. As they were old men, it was difficult for them to dig a grave, so they hired somebody else. But they themselves carried the deceased person, and placed him in the grave. People were buried according to tradition, on a wooden board. The same boards were placed on the sides of the body and on the top. Relations between the Jews and Lithuanians and Latvians were good. A local woman Kukavichute, born in 1895 remembers: “We were very good friends with the Jews, especially with the Grin family, and their daughter. We were invited to her wedding. We sent them hens and ducks, and our close relationship with them was as if we were relatives. When the Soviets first took over, private trade and business, increased at first, as there was a huge demand from the military and civilians from the USSR. Soon they didn't have enough goods. A cooperative authority was created, which controlled private trade and businesses. They placed their representatives in every private business. Large businesses, with good profits were nationalized. Small businesses, were unable to get raw materials and goods, and soon went into bankruptcy. Zeimelis learned about the spread of war into Lithuania, during the morning of June 22nd, as many had radio receivers and could listen to Germany. Molotov was the foreign minister in Stalin's cabinet. After Molotov’s speech, in which he promised to get rid of the fascist German army in two or three days, Jews in Zeimelis started to relax. People did not work on Monday and Tuesday, and gathered in Bazaar Square, to discuss what to do. From Polish refugees, they learned that the Germans were false and that they humiliated and robbed Jews, and forced them to do the most dirty and heavy work. Nobody imagined that they would kill Jews. On Wednesday several army units with heavy equipment passed through Zeimelis. People started to get nervous, and those with horses started to pack their belongings on carts. After some reflection, some of them changed their minds, and returned their belongings to their house. Some of the communists, among them, the Jews Glezer and Baginski, and some Lithuanians, took a local bus and escaped. Most people realized that it was time to leave. On Thursday June 26th 1941, a group of 50 refugees left Zeimelis. Some of them used horses, and some of them walked. My grandparents did not leave. My father, believed that his father, who dealt with Germans, considered them decent people. He suffered under the Communists, during the civil war, and was afraid of them even more than the Germans. There was no real information about German fascists in Lithuania like in the USSR before the treaty with Germany. When Lithuania became a part of the USSR real information about Germany, stopped. Zagorski had a sister in Moscow, and his mother was 75 years old. He told her that he could not remain in Zeimelis, that he was going to live with his sister, and that he would come back in a month or so. His mother told him that she would not leave and added “Well, you can go”. A group of refugees went to Birzaiand from there north to the river Dvina. They crossed the river by ferry. The refugees were saved. Final destiny of the Jews who remained in Zeimelis. During independence years, in a one storied brick house, there was a Jewish bank and a Lithuanian jail. During Soviet times there was a savings bank in this building. There were iron bars on the windows, which even to this day, can be seen. In July 1941, the Zeimelis Jews were housed in this building. “When the Jews were locked in the building of the savings bank, local people threw food through the windows”. These were the words of Jukna, director of the local museum, and Kukavichute. Then all the Jews were transported to a large barn, about 2 kilometers from Zeimelis. This barn was used to house agricultural implements. No Jew was allowed to leave the barn. The Priest, the druggist, the postmaster, the chief of the railroad station were educated people. They were all friends of each other. Priest Kurlyandchik and druggist Shulheifer, frequently played chess with each other. Shulheifer came to Zeimelis about 1920. Rose Abramovich, the owner of the drugstore was without help. Her previous employee had left for Africa. It was very difficult for Rose to run the drugstore by herself, as she was a cripple. She asked the local authorities for help, and they sent her a young druggist named Abrom Shulheifer. He started working for her. Rose was small and not beautiful, and older than Abrom. Despite Rose not been physically attractive, they later got married, and never had children of their own. In 1928 they went to an orphanage in Kaunas and adopted a nine month old boy. The parents of this boy were Jews. The boy's mother died young, and his father had died after falling off a roof. They adopted him and educated him. When he was older, they hired a private teacher from Klaipeda who taught him German. They bought a violin for him which he learned to play. The Zeimelis Priest Kurlyandchik and the Priest from neighboring Lauksodis, agreed that they would try and save this young man. They went to the barn where the Jews were kept, and where the guards were from Lauksodis. The Priests claimed that the boy was not a Jew, and that his parents had adopted him, and nobody knew for sure, if he was a Jew or not. Priests in Lithuania were respected very much by the people, and these two Priests were old with gray hair. Shulheifer confirmed that the boy was adopted and the boy was released to the Priests. During the war years he lived with the priest, and after the war they offered to take him to Kaunas and transfer him to the returning Jews. There is no doubt that the boy was Jewish, he was circumcised and his parents were known. He was then 17 years old and he didn't want to leave the Priests. Later he went to Panavezys, and worked in a military unit, that looked for those people who had helped the Germans during the war. He died in 1988. Near Zeimelis, according to my father, there is a very beautiful pine forest. Next to this pine forest there is a mass grave of about 180 Jews from Zeimelis who were murdered on August 8th, 1941. The Germans had led 3 or 4 Jews at a time to the hole to be shot. Taruts ran away and escaped into the woods. After Taruts escaped, the Lithuanians tied the Jews together with ropes. Some local Lithuanian collaborators from Lauksodis were among those responsible for killing the Jews in Zeimelis. Some of them were jailed after the war and some of them were never convicted. During a visit to Zeimelis in 1982, a local Russian woman, was still very afraid, and refused to tell me anything about this episode. Ozolinsh, who knew my father before the war, told my father, that when they led my grandfather to the hole, where he was to be killed, they wanted him to take off his new coat, but he refused. They tried to take it off, but he resisted. They killed him, but didn't get his coat. Jukna told me approximately the same story. The Jews were forced to undress before being shot. Leizer Chayesh refused to undress. He told them “Shoot me with my coat on”. He was killed and thrown in the hole. Later they thought that probably there was gold in Chayesh’s coat. Some Lithuanians jumped into the hole and started moving dead bodies, trying to find Chayesh. Then their boss showed up and said “What are doing, bury them quickly”. Chayesh was buried with his coat. When my father returned to Zeimelis in 1946, he found one Jewish family there, who came back after evacuation. The mass grave was not marked in any way, and had no monument, or any sign. There was a wooden fence to protect the grave from grazing cattle. A Jewish woman who lived in Zeimelis, said that the fence was put up at the insistence of her family, after they saw cattle grazing there. When I visited the mass grave in 1980, the grave was covered by heavy concrete slabs. Probably the concrete slabs were placed there on purpose, as the rumor was still circulating in Zeimelis, that my grandfather had gold in his fur coat. After the war there was no Jewish community in Zeimelis. In 1956 the synagogue was demolished by order of the authorities. According to an eyewitness all documents were thrown into the river. In a small local museum, headed by the local enthusiast Jonas Jukna, a small exposition devoted to the Jewish Community in Zeimelis was created. One of the local inhabitants gave Jukna a small remnant parchment, of a Torah, about 2 square feet in area. This remnant parchment is a symbol of the Destruction of the Zeimelis Jewish Community. |