Wroclaw, Poland

Edith Stein

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

St. Teresa Benedicta of the Cross, O.C.D.

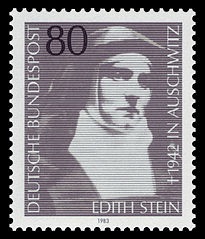

The stamp honoring Stein which was issued in 1983 by the German Postal Service

Religious and martyr

Born

October 12, 1891

Breslau, Silesia, Kingdom of Prussia, German Empire

Died

August 9, 1942 (aged 50)

Auschwitz concentration camp, Nazi-occupied Poland

Honored in

May 1, 1987, Cologne, Germany, by Pope John Paul II

October 11, 1998, Vatican City, by Pope John Paul II

Yellow Star of David on a Carmelite nun's habit, flames, a book

Europe; loss of parents; converted Jews; martyrs; World Youth Day[1]

Controversy

The canonization of a Jewish victim of Auschwitz and the Catholic Church's efforts to convert Jews

Edith Stein

Edith Stein circa 1920

Occupation

Discalced Carmelite nun, theologian and philosopher

Nationality

German

Alma mater

Schlesische Friedrich-Wilhelms-Universität, University of Göttingen

Genres

Subjects

Metaphysics, Logic, Philosophy of mind and Epistemology

Notable work(s)

-

1Finite and Eternal Being: An Attempt to an Ascent to the Meaning of Being

-

2Philosophy of Psychology and the Humanities

-

3The Science of the Cross

Edith Stein, also known as St. Teresa Benedicta of the Cross, O.C.D. (German: Teresia Benedicta vom Kreuz, Latin: Teresia Benedicta a cruce) (12 October 1891–9 August 1942), was a German Jewish philosopher who became a convert to the Roman Catholic Church and later a Discalced Carmelite nun. She is regarded as a martyr and saint of the Catholic Church.

Stein was born into an observant Jewish family, but was an atheist by her teenage years. Moved by the tragedies of World War I, in 1915 she took lessons to become a nursing assistant, and worked in a hospital for the prevention of disease outbreaks. After completing her doctoral thesis in 1918 from the University of Göttingen, she obtained a teaching position at the University of Freiburg.

From reading the works of the reformer of the Carmelite Order, St. Teresa of Avila, Stein was drawn to the Christian faith. She was baptized on 1 January 1922 into the Roman Catholic Church. At that point she wanted to become a Discalced Carmelite nun, but was dissuaded from this by her spiritual mentors. She then taught at a Catholic school of education in Münster.

As a result of the requirement of an "Aryan certificate" for civil servants promulgated by the Nazi government in April 1933, as part of its Law for the Restoration of the Professional Civil Service, Stein had to quit her teaching position. She was admitted to the Discalced Carmelite monastery in Cologne the following October. She received the religious habit of the Order as a novice in April 1934, taking the religious name Teresa Benedicta of the Cross. In 1938, she and her sister Rosa, by then also a convert and an extern Sister of the monastery, were sent to a Carmelite monastery in Echt, the Netherlands for their safety. Despite the Nazi invasion of that country in 1940, they remained undisturbed until they were arrested by the Nazis on 2 August 1942 and sent to the Auschwitz concentration camp, where they died in the gas chamber on 9 August 1942.

Stein was canonized by Pope John Paul II in 1998. She is one of the six patron saints of Europe, together with St. Benedict of Nursia, Saints Cyril and Methodius, St. Bridget of Sweden and St. Catherine of Siena.

Life

Early life

Stein was born in Breslau, in the Prussian Province of Silesia, into an observant Jewish family. She was the youngest of 11 children, and was born on Yom Kippur, the holiest day of the Hebrew calender, which combined to make her a favorite of her mother.[2] She was a very gifted child who enjoyed learning, in a home where critical thinking was encouraged by her mother, and she greatly admired her mother's strong religious faith. By her teenage years, however, Edith had become an atheist.

Though her father had died while Stein was still young, her widowed mother was determined to give her children a thorough education and sent Edith to study at the Schlesische Friedrich-Wilhelms-Universität.

Academic career

In 1916 Stein received a doctorate of philosophy from the University of Göttingen with a dissertation under the philosopher Edmund Husserl, Zum Problem der Einfühlung (On the Problem of Empathy). She then became a member of the faculty at the University of Freiburg, where she worked as a teaching assistant to Husserl, who had transferred to that institution. In the previous year she had worked with Martin Heidegger in editing Husserl's papers for publication, and Heidegger succeeded her as a teaching assistant to Husserl in 1919. Because she was a woman, Husserl did not support her submitting her habilitational thesis (a prerequisite for an academic chair) to the University of Freiburg in 1918.[3] Her other thesis, Psychische Kausalität (Sentient Causality),[4] submitted at the University of Göttingen the following year, was likewise rejected.

While Stein had earlier contacts with Roman Catholicism, it was her reading of the autobiography of the mystic St. Teresa of Ávila during summer holidays in Bad Bergzabern in 1921 that caused her conversion. Baptized on January 1, 1922, she gave up her assistantship with Husserl to teach at the Dominican nuns' school in Speyer from 1923 to 1931. While there, she translated Thomas Aquinas' De Veritate (Of Truth) into German, familiarized herself with Roman Catholic philosophy in general, and tried to bridge the phenomenology of her former teacher, Husserl, to Thomism. She visited Husserl and Heidegger at Freiburg in April 1929, the same month that Heidegger gave a speech to Husserl on his 70th birthday. In 1932 she became a lecturer at the Catholic Church-affiliated Institute for Scientific Pedagogy in Münster, but antisemitic legislation passed by the Nazi government forced her to resign the post in 1933. In a letter to Pope Pius XI, she denounced the Nazi regime and asked the Pope to openly denounce the regime "to put a stop to this abuse of Christ's name."

“

As a child of the Jewish people who, by the grace of God, for the past eleven years has also been a child of the Catholic Church, I dare to speak to the Father of Christianity about that which oppresses millions of Germans. For weeks we have seen deeds perpetrated in Germany which mock any sense of justice and humanity, not to mention love of neighbor. For years the leaders of National Socialism have been preaching hatred of the Jews...But the responsibility must fall, after all, on those who brought them to this point and it also falls on those who keep silent in the face of such happenings.

Everything that happened and continues to happen on a daily basis originates with a government that calls itself 'Christian.' For weeks not only Jews but also thousands of faithful Catholics in Germany, and, I believe, all over the world, have been waiting and hoping for the Church of Christ to raise its voice to put a stop to this abuse of Christ’s name. —Edith Stein, Letter to Pope Pius XI

”

Stein's letter received no answer, and it is not known for sure whether Pope Pius ever even read it.[5] However, in 1937 the pope issued an encyclical, written in German, Mit brennender Sorge (With burning Anxiety), in which he criticized Nazism, listed breaches of the Concordat signed between Germany and the Church in 1933, and condemned antisemitism.

Discalced Carmelite nun and martyr

Stein entered the Discalced Carmelite monastery St. Maria vom Frieden (Our Lady of Peace) at Cologne in 1933 and was given the religious name of Teresa Benedicta of the Cross. There she wrote her metaphysical book Endliches und ewiges Sein (Finite and Eternal Being), which tries to combine the philosophies of Aquinas and Husserl.

To avoid the growing Nazi threat, her Order transferred Stein and her sister, Rosa, who was also a convert and an extern Sister of the community, to the Discalced Carmelite monastery in Echt in the Netherlands. There she wrote Studie über Joannes a Cruce: Kreuzeswissenschaft ("Studies on John of the Cross: The Science of the Cross"). Her testament of June 6, 1939, states, "I beg the Lord to take my life and my death … for all concerns of the sacred hearts of Jesus and Mary and the holy church, especially for the preservation of our holy order, in particular the Carmelite monasteries of Cologne and Echt, as atonement for the unbelief of the Jewish People, and that the Lord will be received by his own people and his kingdom shall come in glory, for the salvation of Germany and the peace of the world, at last for my loved ones, living or dead, and for all God gave to me: that none of them shall go astray."

Ultimately, however, Stein was not safe in the Netherlands—the Dutch Bishops' Conference had a public statement read in all the churches of the country on 20 July 1942, condemning Nazi racism. In a retaliatory response on July 26, 1942, the Reichskommissar of the Netherlands, Arthur Seyss-Inquart, ordered the arrest of all Jewish converts, who had previously been spared. The Stein sisters were arrested at the monastery. On 7 August, early in the morning, 987 Jews were deported to Auschwitz. It was probably on 9 August that Stein, her sister, and many other of her people, were gassed.[2][6]

Legacy and veneration

Memorial to Edith Stein in Stella Maris Monastery, Haifa, Israel

The Martyrdom of Edith Stein depicted in a stained glass work by Alois Plum, in Kassel, Germany

Memorial to Edith Stein in Prague, Czech Republic

Edith Stein in a relief by Heinrich Schreiber in the Church of Our Lady in Wittenberg, Germany

Stein was beatified as a martyr on 1 May 1987, in Cologne by Pope John Paul II and then canonized by him 11 years later on 11 October 1998. The miracle which was the basis for her canonization was the cure of Teresa Benedicta McCarthy, a little girl who had swallowed a large amount of paracetamol (acetaminophen), which causes hepatic necrosis. Her father, the Rev. Emmanuel Charles McCarthy, a priest of the Melkite Greek Catholic Church, immediately rounded up relatives and prayed for Stein's intercession.[7] Shortly thereafter the nurses in the intensive care unit saw her sit up completely healthy. Dr. Ronald Kleinman, a pediatric specialist at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston who treated Teresa Benedicta, testified about her recovery to Church tribunals, stating "I was willing to say that it was miraculous."[7] McCarthy would later attend Stein's canonization ceremony in the Vatican.

Today there are many schools named in tribute to Stein, for example in Darmstadt, Germany,[8] Hengelo, the Netherlands,[9] and Mississauga, Ontario, Canada.[10] Also named for her are a women's dormitory at the University of Tübingen[11] and a classroom building at The College of the Holy Cross in Worcester, Massachusetts.

The philosopher Alasdair MacIntyre published a book in 2006 titled, Edith Stein: A Philosophical Prologue, 1913-1922, in which he contrasted Stein's living out of her own personal philosophy with Martin Heidegger, whose actions during the Nazi era according to MacIntyre suggested a "bifurcation of personality."[12]

In 2009 her bust was installed at the Walhalla Memorial near Regensburg, Germany.

Jewish-Catholic controversy

The beatification of Stein as a martyr generated criticism and created some controversy. Critics argued that Stein was killed because she was Jewish by birth, rather than for her later Christian faith,[13] and that, in the words of Daniel Polish, it seemed to "carry the tacit message encouraging conversionary activities" because "official discussion of the beatification seemed to make a point of conjoining Stein's Catholic faith with her death with 'fellow Jews' in Auschwitz".[14][15]

The position of the Roman Catholic Church is that Stein also died because of the Dutch episcopacy's public condemnation of Nazi racism in 1942; in other words, that she died for the sake of the moral position of the Church, and is thus a true martyr.[16][2]

Writings that have been translated into English

-

•Life in a Jewish Family: Her Unfinished Autobiographical Account, translated by Sister Josephine Koeppel, O.C.D., from The Collected Works of Edith Stein, Volume 1, ICS Publications, 1986

-

•On the Problem of Empathy, translated by Waltraut Stein, from The Collected Works of Edith Stein, Volume 3, ICS Publications, 1989

-

•Essays on Woman, translated by Freda Mary Oben, 1996

-

•The Hidden Life, translated by Sister Josephine Koeppel, O.C.D., 1993[17]

-

•The Science of the Cross, translated by Sister Josephine Koeppel, O.C.D. The Collected Works of Edith Stein, Volume Six, 1983, 2002, 2011, ICS Publications

-

•Knowledge and Faith

-

•Finite and Eternal Being: An Attempt to an Ascent to the Meaning of Being

-

•Philosophy of Psychology and the Humanities, translated by Mary Catharine Baseheart, S.C.N., and Marianne Sawicki, 2000

-

•An Investigation Concerning the State, translated by Marianne Sawicki, 2006, ICS Publications

-

•Martin Heidegger's Existential Philosophy,[18] translated by Mette Lebech, 2007

-

•Self-Portrait in Letters, 1916-1942

-

•Spirituality of the Christian Woman,[19] from The Collected Works of Edith Stein, Volume Two, Essays on Woman, 1987, ICS Publications

-

•Potency and Act, Studies Toward a Philosophy of Being Translated by Walter Redmond, from The Collected Works of Edith Stein, Volume Eleven, 1998, 2005,2009, ICS Publications