| 23. Yehi Am and the November 29 UN Resolution | ||

|

Since no vehicle could access the hill of boulders, we were forced to carry everything needed for the construction of a minimal shelter for the pioneer group at the foot of the fortress, cement, sand (in sacks), lumber, corrugated metal sheet—and food as well. It was a merry climb, despite our heavy loads. Almost the whole population of the kibbutz took part, a difficult task even for experienced scouts. We succeeded in reaching the top of the hill, out of breath but dry, and secured our precious load in hidden niches of the ancient ruins before a heavy cloudburst forced us to hide ourselves in another shelter. There, dry but stooping, we discussed the important items on our planned agenda while the rain poured on: We had to meet the kibbutz lorry, which was to return us to our tent camp. It was waiting for us at the point where the dirt path met the paved road. One of our Eretz Yisraeli haverim, who had accompanied us as a guide, claimed that he knew the path leading to the road, but this proved to be an illusion. The rain had washed away every trace of the path we had used on our way up. We were trudging along in a sea of mud without any means of orientation, our clothes and shoes soaked through to the very bone. Heavy, dark clouds hid the sun, and we cold not even guess the direction we were heading, when suddenly an Arab riding his donkey emerged out of the rain. As our guide spoke Arabic, he understood that the rider was on his way to Tarshiha, a nearby Arab village which, however, was commonly known to be unfriendly to the Jewish settlers. Nonetheless we asked him, through our interpreter, to lead us to his village and, moreover, to let Naomi, one of our girls who had difficulty walking further, ride his donkey. After a while our group of 15-20 youngsters reached the paved road near the Tarshiha’s police station, but the moment we appeared in front of the gate, the station’s alarm sirens came on, and a dozen policemen in red berets appeared with heir Tommy guns pointing at us. They ordered us not to move, suspecting that we had planned to attack the station. (Such events did happen in those days!) It took a while before they became convinced that we had no malicious intentions and gave one of us permission to enter the station and make a call, informing our lorry driver of our whereabouts. While waiting for his arrival, we danced a stormy hora and sang Zionist marches in the pouring rain. At long last we reached home, but it was not easy to get dry in our half-tent. On November 29, 1947, a special session of the United Nations General Assembly at Lake Success in the State of New York discussed the recommendations of its Special Committee for Palestine. This committee was to investigate and recommend a solution to the “Palestinian Question”, in view of the immense masses of “displaced persons” to whom the British adamantly refused entry into Eretz Yisrael and thus languished in European camps. The Committee recommended almost unanimously that the British Mandate over Palestine be terminated, and that the area in question be divided into two independent political entities: a Jewish state and an Arab state. To become binding, the resolution had to be approved by the votes of at least two thirds of UN members. The whole kibbutz followed the progress of the voting tensely listening to its single wireless. One climactic surprise of that UN session was the sensational speech of Mr. Alexander Gromiko, representing the Soviet Union, which, until then, had regularly taken a pro-Arab and anti-Zionist stand on every issue concerning the Middle East. The Russian diplomat’s speech made a surprising turn-about by emphasizing the right of the long-suffering Jewish people to a homeland of their own. He voted in favor of the recommendation, along with the whole “Soviet bloc”, except Yugoslavia, which abstained. The expected vote was cast not as a sudden embrace of the Zionist idea but rather as an indictment of British colonialism. While the voting went on, we responded to every YES vote with joyful cries, and with deep sighs of dismay to every NO we heard on the broadcast. The Arab states vehemently opposed the committee’s recommendation, with the usual support of the “Third World,” mostly Muslim and developing countries of Asia and Africa. The last vote was decisive for reaching the necessary majority, increasing our tension and dramatizing the situation. Contributing greatly to the outcome, by convincing other delegates to vote YES, were Prof. Fabrigat, chairman of the session, and Dr. Granados, as delegates of two South-American countries, Uruguay and Venezuela, respectively. I do not remember which state cast the last vote, but when we heard it to be YES, we started a spontaneous hora, as did crowds of thousands in the streets all over the country. For the first time in history, after two millennia of Diaspora, of hatred and persecution, the Christian world had recognized our right to our own homeland. The Arab response was immediate and violent. All the Arab states, as well as the leadership of the local Arab population, rejected the resolution. They declared that they would never tolerate the establishment of a Jewish state and that they would fight it. The local Arabs started terror actions against Jewish settlements, villages and towns. They attacked the interurban traffic and tried to cut off the main road between the Lowland and Jerusalem. “Jerusalem has mountains around her,” sings the Psalmist. Now there were Arab terrorists lurking on the slopes of those mountains, which control the at that time narrow road, attacking the convoys that brought provisions and reinforcements to Jerusalem. The city was short on food and water and badly needed more fighters. In Jerusalem, as well as in other mixed-population towns, the armed Arab population attacked the Jewish parts, and the situation deteriorated into a veritable civil war. Rusting skeletons of vehicles, which those rioters had destroyed and burned with their passengers and loads still inside, lined both sides of the road, all along Shaar Hagay (Bab El waad), as witnesses of the heavy battles conducted on the road to the besieged ancient capital. In spite of the open British support of the rioters, Palmach units commanded by Yitzhak Rabin conquered the surrounding Arab villages and managed to open the road and so to liberate Jerusalem. The manager of the Kiryat Shmuel transit camp, where Mother was lodged, informed her that she was to share a room with another woman in Rehovot. Since we had planned for her to live with us after these many years of separation, the kibbutz had reserved a nice room for her with the option of cooking for herself in case she refused to eat the non-kosher food of the kibbutz kitchen, but she had left he transit camp before we got there to fetch her. I caught the first bus to Rehovot to bring her back, but Rehovot was already too big a place to find somebody without a known address. Fortunately, while walking along the city streets and thinking of ways to find her, like in fairytales with a magic wand I caught sight of her, walking on the opposite sidewalk, smiling to herself and enjoying her new freedom under the blue sky of Eretz Yisrael! I rushed to her happily, telling her that I had come to fetch her and bring her back to us. Overjoyed to have met by chance, we took a bus to Ramat Yitzhak, where Shoshsa had rented a sublet room after leaving kibbutz Negba. However, we faced a problem. On one hand we could not leave Mother to the exclusive care of Shosha, who had to work hard for her living; on the other hand, Mother refused to live in the kibbutz. We petitioned the Social Committee of the kibbutz to grant her a minimal monthly allowance, sufficient for a modest living, but it was rejected as unaffordable. To let Mother stay with us we had to shoulder responsibility ourselves and to leave the kibbutz. Haya had been waiting a long tome for this to happen. Although the communal lifestyle was not her cup of tea, she had been performing her daily duties in the kibbutz, excellently, without complaint and with justly earned high esteem. I knew that she had endured kibbutz life only for my sake. We had discussed this delicate issue not just once, and I had always argued that it was important for me to stay. Having taught and convinced many youngsters to choose this way of life, how could I renounce my own value system so easily? She used to give in to my arguments, and I appreciated her sacrifice, loving her ever so much more for it. It was a hard decision for me to make, but ultimately the fifth Commandment, “Thou shalt honor thy father and thy mother”, proved stronger than any other doctrine or ideology. To forsake Mother was out of question and, as in many other issues, I totally identified with Haya in this decision. Her love for her mother was above every other consideration, and Mother’s fate and well being had become my personal concern as well.

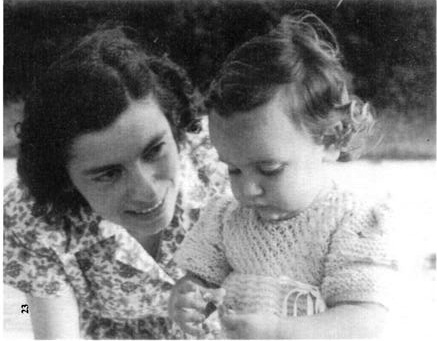

Haya was awaiting a baby at the end of January, and she was allowed to stay in the kibbutz until her delivery, whereas I left in mid-December (1947) for Ramat Gan (a “satellite town”, North-East of Metropolitan Tel-Aviv), where Shoshsa’s husband, Lajos, my one-time neighbor and school mate in Nagymagyer, helped me not only to find a decent job as maintenance man in a local chocolate factory, but also through his widespread connections in town, to rent a little (1½-room) apartment. We (Mother and I) moved into it in January 1948 and, while impatiently awaiting news from Haya, tried to make it cozier and more habitable for her and the baby. As the theoretic day of delivery arrived, we grew more anxious, especially since phone calls were practically out of question during those early nation-building days. At last, on February 3 we got a telegram: “A baby girl was born, both are well.” I was extremely sorry and frustrated that I could not be near Haya during her hours of labor pains and suffering, but traveling by bus was highly dangerous in those days. The entrance to Haifa and a section of the road between Haifa and Kityat Haim were within shooting range of Arab rioters. Haya, brave and rational as ever, had pleaded with me not to endanger myself. Not until mid-February, when Alisa (named after my dear mother Elsa) was two weeks old, did I get to see our little darling and was overwhelmed. Haya had not exaggerated her beauty. During feeding time, the other mothers could not take their eyes off our little girl. The last feeding done, to the full satisfaction of this tiny package of beauty, we got our last instructions from the nurse and bid farewell to the kibbutz. We passed dangerous sections in armored buses. While we heard bullets hitting the armor from all directions, I held my precious sleeping load in my lap, protecting her instinctively with my body. After we reached a safe area, we changed to a regular bus, which let us off in Ramat Gan. We still had quite a stretch to walk home. While Haya walked with Alisa in her arms, demanding her overdue natural rights, at the top of her lungs, I carried our belongings in two suitcases. At last we entered home, where Mother was waiting eagerly at the doorstep—the happiest person on Earth as she welcomed her new granddaughter. With tears of joy running down her shining cheeks, she embraced the baby, and Alisa was hers forever. |

||