| 17. Escape, Glass House and Rescue of People | |||

|

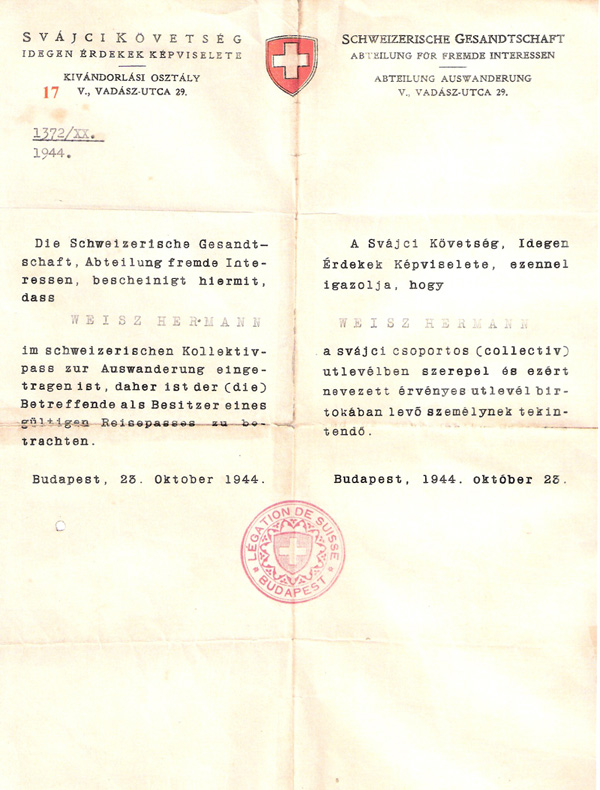

We stood there on the riverbank, 17 determined tough young men, who undertook that risky adventure, in spite of being aware that there was no time for sentiment, we could not tear ourselves away from that somber mass of water that had just taken away our past, our identity and our dearly cherished memories. The arrival of our "messenger" with the tickets brought us back to reality. While distributing them he advised us to disperse in different wagons and to sit separately so we would not endanger each other in case anyone were caught by military police checking the passengers. He also instructed us to leave the train at Kelenföld, one station before the Keleti (Eastern) terminal where many policemen were watching to catch illegal travelers, including forced-labor deserters. While waiting for the train that was to take us away, we became aware that none had arrived the whole day, and none had left our switchyard, a strong indication that the rails all around could have been destroyed. We had to be gone before the first overnight train arrived with the first light of dawn, and before our company notices our absence in the morning. The tension was unbearable. It had started to rain and that even further increased our depression. Toward midnight we saw a locomotive pulling and pushing several wagons together to assemble them into a train. We watched intensely for which end of the assembly it would ultimately start to pull. Left meant south, toward Budapest, right was to the North, into Slovakia. We prayed of course that it would be toward Budapest. After much nervous irritation, we were relieved to see it pointing southward. As passengers started to board the wagons, we did likewise in groups of three or four into each wagon. We passed military police patrolling the area without looking directly at them and went on indifferently as though they were transparent and of no concern. The stranger (I never learned his identity) remained with me and sat next to me. When we left the train at Kelenföld, as planned, he took me to his place as a temporary hideout. Later he told me that all of our 16 escapees had arrived in Budapest safely and had been lodged in secure hideouts. I could not remain with him much longer, because his concierge insisted that I be registered at the nearby police station, which was of course out of question. My anonymous host thereupon took me to the "Glass House" at 29 Vadász-utca. The Glass House, which belonged to the Arthur Weiss family, had served since its inception as a wholesale store for windows, mirrors and other glass-based building components, which were always on display. In July 1944 the house achieved "exterritorial" status as the Emigration Department and Foreign Interests Agency of the Swiss Embassy. Even the Szálassy regime generally respected it as an off-limits premise. In practice it also served as meeting place for the Rescue and Relief Committee, which comprised representatives of all branches of Judaism in Hungary, including the Zionist movement. The leadership of the resistance and rescue mission of Zionist youth movements likewise sometimes held their meetings at the Glass House. "Emigration Department" was not a fictitious name. As the representative of British interests, the Swiss Embassy obtained the consent of Hungarian authorities for the emigration of 7,800 Jews from Hungary to British-Mandate Palestine and issued a collective passport for them. Everybody listed in it was considered a foreign citizen, entitled to the protection of this department, and thus removed from Hungarian jurisdiction. To legitimize their status, the embassy (to be precise the consul, Mr. Carl Lutz) issued each of them a special Schutzpass (Certificate of Protection). Under the logo of the Swiss Embassy, it had a bilingual, German and Hungarian text:

Most of the persons registered in the collective passport were accommodated in the "Protected Houses" (Safe Houses) along Pozsonyi utca, instead of the Ghetto or in one of the "Jewish Houses" branded by a yellow Star of David. The Protected houses likewise enjoyed exterritorial status and were off-limits to Hungarian officials. Since the possession of a Schutzpass afforded nominal protection from the atrocities of Nyilaskereszt (Arrow Cross) gangs, expert "duplicators" in our rescue group succeeded in making exact copies, which were distributed among over 50,000 Jews. Our volunteer couriers quickly spread all over the country, to forced-labor units and to ghettos and to branded Jewish houses of Budapest, distributing this life-saving piece of paper. Thousands of forced laborers who had escaped their units and came to the capital were thus saved. Many couriers on motorcycles raced to overtake the columns of inhumane "death marches" on the road to Austria, on which Jews were driven in freezing weather without food and drink, in inadequate clothing and water-soaked shoes. Our brave couriers succeeded in handing out Schutzpasses clandestinely and thus to extract hundreds, if not thousands, from the marching columns, who could then return to the relative safety of Budapest. Many civilian Jews likewise owe their lives to these forged Schutzpasses. Even some members of the Hungarian underground resistance made use of them for their protection. The forged documents resembled the genuine ones so well that even the forgers could hardly tell them apart. The Hungarian authorities, concerned on an apparent flood of Schutzpasses, demanded a definitive list of the 7,800 authentic names in the collective passport. The Swiss Embassy, in turn, requested the same of the Jewish Rescue Committee, which promised time and again to submit such a finalized list as soon as its people were finished working on it. When I arrived in the Glass House, I saw some people dealing with long lists of names and was myself given a job of copying lists. At that time I did not know what this was about; only some time later did I understand that no list would ever be submitted to the embassy, and that the latter was graciously turning a blind eye to the widespread use of those documents bearing the embassy stamp, with the tacit knowledge of the consul, Mr. Carl Lutz. The source of mass-produced Schutzpasses was the "mobile workshop" of the Resistance and Rescue organization of the Zionist Youth Movements, which prepared all kinds of forged documents of civilian, military, police and even some of German authorities, including the Gestapo. It was the same organization to which our group of forced-labor escapees owed our new personal identification papers. (My forged identity was, for instance, Horvát Vincze, born in Gyöngyös, May 15, 1922, Protestant. I had to memorize the names of the parents and many relatives of my "new family").

Distribution of these documents was obviously dangerous. The task fell to courageous volunteers who endangered themselves daily to rescue Jews from the claws of (allegedly) human bloodhounds. Among the volunteers I remember in particular three young men who worked in that workshop: David Grosz (Daividke), Avri Feigenbaum (Feigi) and Micky Langer. Saying that they "worked" is a vast understatement that minimizes their truly selfless contributions. On receiving an "order", they did not heed day or night, neither food nor sleep; they simply kept on working until the job was done and the product of their workmanship delivered to its destination. They were fully aware of the tremendous, life-saving responsibility of their pursuit, yet had to be very cautious and constantly alert lest neighbors suspect something. It happened several times that, after leaving a place, detectives arrived within minutes, looking for them. Although I lack precise statistics, I am sure that they produced and distributed thousands and thousands of all sorts of documents in different languages, for persons in danger in general, and for members of the resistance in particular, in addition to the tremendous masses of Schutzpasses mentioned above. It is no exaggeration that they were the real heroes of our resistance, rescuing people during that gloomy period of history. Unfortunately, they were once caught, just as they moved into a new place, with the whole "workshop" packed into six suitcases, by a couple of detectives who were waiting for them with drawn pistols and malicious grins of joy on their gloating faces. Later, the masters of third-degree interrogation in the infamous Margit Körút jail made utmost efforts to make these stubborn Jewish rebels talk, to put an end to that sophisticated underground organization, which had caused them plenty of trouble with ridiculously primitive equipment! The boys were cruelly beaten and tortured like victims of the Medieval Inquisition, but in vain. Not one of them uttered a word those bestial sadists could use. They neither disclosed their real names, nor revealed anything concerning the Resistance Organization. Unfortunately, Micky paid for his stubborn silence and for the thousands of human lives his devoted toil had saved. He was beaten to death and ended his life as a hero in his friend's arms. We shall preserve and cherish the precious memory of his martyrdom in our hearts forever. Besides these three heroes, several other friends of the Resistance Organization were brought into this terrible jail. One day, after the siege of Budapest by the Soviet Red Army was tightened, the wardens ordered a sudden lineup of all prisoners in the jail's courtyard. An army officer holding a sheet of paper shouted at them, "Listen, you bastards, everyone hearing his name, step forward!" He started to read the names of our people, but no one moved until Daividke, surprised at hearing his special alter-ego name, Rapos known only by Moshe Alpan (Pil), one of the top men of the organization, which nobody else could have known, understood that the officer was connected with Pil and had been sent by him. As he stepped forward, so did all the others now as their names were called again. The wardens present were astonished, because they were sure that all the named prisoners were going to be executed. One of them was even heard saying, "Why bother? We can finish this here." The officer ignored him and led the whole group outside the gate. Then they marched as quickly as the tortured prisoners could walk. They passed the Lánchíd (Chain Bridge) across the Danube from Buda to Pest and, led by Daividke, reached Number 17 Wekerle Street, a safe house where we had impatiently and anxiously awaited their arrival. It is hard to describe the outbreak of joy and elation as we welcomed them with joyful hugs and kisses. Only the tragic death of our brave Micky beclouded our joy. Their liberation was an outstanding manifestation of fidelity and friendship; it proved that no price was too high and no risk too grave when the fate of our khaverim was at stake. |

|||