During the dark, desperate days of the Great

Depression, the government selected Central Jersey

as the site of a bold, unprecedented experiment in

stimulus spending. With

the jobless rate hovering near 25 percent, dozens of

emergency anti-poverty initiatives were introduced

through various New Deal agencies.

Originally known as Jersey Homesteads, Roosevelt was

one of ninety-nine communities across the country

created by the federal government as part of a New

Deal initiative. In early 1933, the National

Industrial Recovery Act (NIRA) created the Division

of Subsistence Homesteads, the purpose of which was

to decentralize industry from congested cities and

enable workers to improve their standards of living

through the help of subsistence agriculture.

Jersey Homesteads was unique, however, in that

it was the only community planned as an

agro-industrial cooperative which included a farm,

factory and retail stores, and it was the only one

established specifically for urban Jewish garment

workers from New York, many of whom were committed

socialists.

Incorporated on May 29, 1937, the settlement was

like an American kibbutz, the countryís first and

only secular Jewish commune funded by US

government.

|

The land for the community is

located in Millstone Township, Monmouth

County, New Jersey (not far from

Hightstown).

The organizers took applications for 200

settlers at $500 to buy into the

co-operative community.

Five hundred acres of the 1,200 acre

tract were to be used for farming, and

the remaining portion for 200 houses on

1/2 acre plots, a community school, a

factory building, a poultry yard and

modern water and sewer plants.

Jersey Homesteads' buildings are

characterized by their spare geometric

forms and use of modern building

materials (including cinder blocks).

The houses are integrated with

communal areas and surrounded by a

green belt.

This is a view of Jersey Homesteads in

the 1930s.

|

International

Ladies' Garment Workers Union agreed that

the Jersey Homesteads factory would be a new

cooperative run by the settlers themselves,

so that no union jobs would be removed from

New York. The factory opened in 1936.

The Workers' Aim Cooperative Association had

overall responsibility for the factory: the

trade name for its products was Tripod,

signifying the triple cooperative (factory,

farm and retail stores).

The retail stores--a clothing store, grocery

and meat market, and tea room--were run by

the Jersey Homesteads Consumers' Cooperative

Association.

The garment factory failed within two years.

Because of delays in housing construction

and the resulting shortage of workers, the

first year was disappointing. The

workers actually went on strike at one

point, even though they owned the factory

and there was no upper management to

protest. They had gone on strike against

themselves, picketing their own

company. The factory was declared a

failure in 1939 by the Farm Security

Administration which attempted to auction

off the assets.

By early 1940, having failed to auction the

factory fixtures, negotiations with

Kartiganer and Co. succeeded and the company

began operations at the Jersey Homesteads

factory. Proving to be no more economically

successful than the factory, the

settlement's agricultural cooperative ceased

operations in 1940. Although the clothing

store failed with the factory, the borough's

cooperative grocery and meat market endured

into the 1940s.

|

The farm, consisting of general, poultry

and dairy units, was known as the Jersey

Homesteads Agricultural Association, and,

like the other cooperatives, was run by a

board of directors.

With a shortage of

green thumbs within the community, the

crops wilted. The former city dwellers

didnít till the soil enthusiastically.

|

Despite

conflicts and hardships, the residents of

the borough did manage to build a

close-knit community--working, playing and

developing the land together. Indeed, in

the late 1930s the Community Manager,

through the Works Progress Administration

(WPA), developed recreational programs of

adult education, arts and crafts, and

founded a library. The borough also had

many clubs and societies.

The Orthodox synagogue (Congregation

Anshei Roosevelt, later affiliated with

Conservative Judaism) did not seem to be

of central importance but religious

services were held at various locations

until a synagogue was built in 1956. Many

of the homesteaders spoke Yiddish and, in

general, all nurtured the community.

|

|

Artist Colony

In 1936, the artist Ben Shahn was invited to

paint a mural on the wall of the school

depicting the founding of Jersey Homesteads.

Ben Shahn and his wife Bernarda Bryson

settled permanently in Roosevelt in 1939 and

attracted other artists, including former

chairman of the Pratt Institute's Fine Arts

department Jacob Landau; painter Gregorio

Prestopino and his wife artist Liz Dauber;

graphic artist David Stone Martin and his

son wood engraver Stefan Martin;

photographers Edwin and Louise Rosskam; and

others.

Additional artists associated with Roosevelt

are pianists Anita Cervantes and Laurie

Altman, opera singer Joshua Hecht and

writers Benjamin Appel, Shan Ellentuck and

Franklin Folsom.

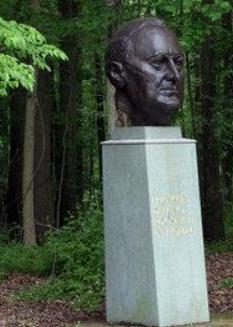

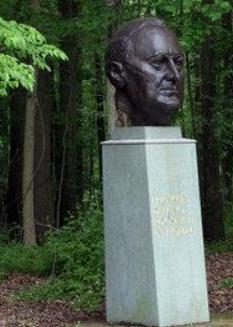

It was Ben Shahn who had the original idea

to build a monument to Franklin D. Roosevelt

in 1945. In 1960, on the eve of the

borough's 25th anniversary, a new Roosevelt

Memorial Committee was formed which was

able, through fund-raising and donated

labor, to create a memorial to the man who

was seen as the town's inspiration. Ben

Shahn's son Jonathan sculpted a bust of the

president.

|

|

Borough

of Roosevelt Historical Collection - Rutgers

University Library

|