Harold Frederic, a New York Times reporter whose dispatches from Russia were

collected and published as a book in 1892, watched the scenes at the railway

station when the tightly packed Third Class carriages left Moscow. Almost all

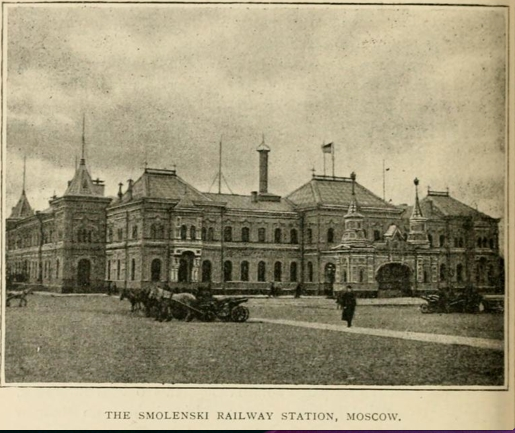

refugees took the slow, inexpensive train that left the Smolensk Station at 7 p.m.

each evening:

The long, broad platform was dotted with

piles of their luggage heaped against the

walls... There were pet pieces of furniture

wrapped up in sheets and crockery encased

in bedding and tied with ropes. One saw

carpets, picture-frames, candlesticks, big

leather-bound books, even birdcages, all

made into parcels as portable as possible...

Everywhere there were teapots fastened

outside the hand luggage, so as to be easy of

access during the wearisome journey...

(1892, p.199)

The long, broad platform was dotted with

piles of their luggage heaped against the

walls... There were pet pieces of furniture

wrapped up in sheets and crockery encased

in bedding and tied with ropes. One saw

carpets, picture-frames, candlesticks, big

leather-bound books, even birdcages, all

made into parcels as portable as possible...

Everywhere there were teapots fastened

outside the hand luggage, so as to be easy of

access during the wearisome journey...

(1892, p.199)

Frederic not only described day-to-day reality as the Moscow Evictions progressed,

but also reported on the experiences of refugees who emigrated, travelling from

central

Russia to the German port of Hamburg. The "New Exodus," as the New York

Times called it, began in June of 1891. During that summer, between two and three

thousand families per week received help from the Hamburg Jewish community. In

July, volunteers served 14,128 meals to Jewish families waiting at the port; 23,579

were served in August. According to Frederic, the numbers peaked on 4 August,

when 1,360 refugees were fed in one day. Of particular interest to family researchers

is Frederic's list of 88 persons evicted from Moscow in 1891, naming their towns of

origin in the Pale (1892, pp.291-292).

Sources and Further Reading

Harold Frederic's original dispatches are reprinted in the New York Times archive.

See, for example "AN INDICTMENT OF RUSSIA" by (London Correspondent) Harold

Frederic, The New York Times, 7 December 1891, p. 1.

Frederic's book, The New Exodus: A Study of Israel in Russia (1892) is available in

digital form (free of charge) through The Internet Archive.

Map Showing the Percentage of Jews in the Pale of Settlement and Congress Poland

from The Jewish Encyclopedia, 1905. In public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

from Wikimedia Commons.

Map of European Railroad Routes and Stations, with inset showing Moscow-St.

Petersburg line. Courtesy of David Rumsey Historic Map Collection.

1914 - 1936 Recovery, Then Purges

|