Although she performs as if she is 39, this December marks the ninety-eighth birthday of my grandmother, Sarah (AKA "Nanny") who carefully keeps track of her 4 children, 14 grandchildren, and 17 great-grandchildren from her telephone at Shalom Park in Southeast Denver. In 1901 she was born in a village which she refers to as "Majdan near Kolbuszowa," a shtetl in Southern Poland, and immigrated to Memphis in her early childhood before moving to Denver in 1923. Since 1990, I have researched my family history by visiting the National Archives in Washington, D.C. where I found the immigration record of Sarahís husband, my grandfather Max, who arrived at Ellis Island on the morning of March 20, 1909, from Tarnow, Poland, at the age of 18 with only $2.50. I also searched the Holocaust section of Jewish libraries for the location of the shtetls of both Max and Sarah, and finally through the internet site at Jewishgen.org, I discovered a database of people throughout the world providing first-hand information on the towns where their ancestors lived. My research culminated last May when I had the opportunity to return to both Majdan-Kolbuszowa and Tarnow. A few of the highlights of my visit follow which I share in the hope that it may inspire others whose families are from Eastern Europe to perhaps also search for their roots.

I. Kolbuszowa: (Click here for Kolbuszowa photos)

Through my research I discovered a book about Kolbuszowa, Sarahís birthplace, by Norman Salsitz, 79, a Holocaust survivor who lives in Springfield, New Jersey. I met him at his home on my way to Poland. He explained that before World War II there were approximately 2,000 Jews in Kolbuszowa; except for nine Jews who had fled to the forest, all were murdered in the Holocaust. After the war, these survivors moved to Palestine or to the United States. He hesitantly admitted that one fellow Jew, Jacob Plafke"witcz" wished to remain in Kolbuszowa. Converting to Catholicism, he had added the "witcz" to his name, in order to assimilate in what continued to be a largely unsafe atmosphere for Jews. Norman also gave me the address of Helena Dubicia, a Polish woman in Kolbuszowa who was once the town historian. My plan was to visit both Jacob and Helena.

Two days after my visit with Norman, I rented a Nissan-Micro in Krakow, Poland and drove 130 kilometers east to Kolbuszowa. With me was my translator, Magdalah Bartosz, nicknamed Magda, who was fluent in English and Polish and is a graduate student at the University of Krakow majoring in Judaic studies. She works at a Jewish bookstore in Krakow, located in the former Jewish quarter, not far from where Schindlerís factory still stands. Upon entering Kolbuszowa I noticed a large welcome sign, a coat of arms. The sign had two hands clasped with a yellow Star of David below and a white cross above symbolizing the unique coexistence between Poles and Jews which had once prevailed in Kolbuszowa. I headed directly to the former synagogue. I discovered it was locked. Magda asked a nearby Polish man who was hanging clothes from his second story apartment balcony how we could gain entry. He pointed to a home across the street and mentioned that the woman who lived there knew how to get the key.

At the home, a Polish girl told us that her mother who had the key would be returning from work at any minute. Indeed, as we spoke the mother returned. She explained that she worked for the town registry, but that we would have to return tomorrow to her office to obtain the key. She also described how the Nazis arrived in September, 1939, and how they converted the area in which we were standing into the ghetto. Through her, I came to understand that there is little interest and few visitors that inquire about the now deceased Jewish community. She sounded as if she was the only one that continued to keep an eye on the former synagogue, and, aside from the Jewish cemetery, there are no other remains of what was once an active Jewish community.

I then asked her if she knew of the Jewish man who had converted to Catholicism following WWII. At first, she nodded no. I realized, however, I had pronounced the name incorrectly so I opened a folder in which Norman had written the name of Jacob Plafkewitcz and showed it to her. Her entire expression changed as if she had some haunting image flashing before her. She told us that Jacob was her father and died just over a year ago.

Thus the entire relationship between this woman and the deceased Jewish community took shape. Her father was the last Jew in Kolbuszowa, and this woman, who by no coincidence was the only resident to tend to the former synagogue, knew that she is the only descendent of a Jewish person living in this town. While I was very surprised to put this puzzle together, I can only imagine her reaction to having a young foreigner from Denver, Colorado arrive at her doorstep in a rural town in Southern Poland and ask about the now extinct Jewish community and the whereabouts of her recently deceased father.

II. Majdan: (Click here for Majdan photos)

Not far from the synagogue was the residence of Helena Dubicia, the former town historian. Magda and I knocked on her door and, upon hearing that I was from the U.S. and knew Norman, she invited us into her home. I immediately noticed that her home was packed with goods: extra dishes, furniture, flowerpots and other basic furnishings. Helena, our host, confirmed my suspicion. Like the current residences of many Poles, she told us that this home was formerly occupied by a Jewish family which explained why the living and dining room was filled with many more household items than Helena would need. When the Jews of Kolbuszowa were forced to leave their homes for the larger ghetto of Rzeszow during the Holocaust, they often had no time or room to pack all but a few personal items.

Putting my personal feelings about my surroundings aside, I listened while Helena told us that she was fourteen when the Nazis arrived in Kolbuszowa in 1939. Soon after the ghetto was constructed she would pass milk through a secret opening to her Jewish friends. I did not ask, nor did she say, what she expected in return for the milk. While some Poles helped Jews during the war, others provided help only in exchange for large payments of cash or jewelry.

I then told Helena of my grandmotherís family, some of who remained in this area until WWII. To my surprise she recalled that a relative of mine owned a grocery store on the road that ran between the main square and the Jewish cemetery located four kilometers to the east. To me it was a rare opportunity, only the most senior of citizens living in this town would remember any Jews and my relatives from before WWII. It was with mixed emotion that I learned of my family from Helena. On the one hand, I realized that Helena, like most of the residents, may have done little to help the Jews escape their fate, on the other hand, she was one of the last people who could provide me first-hand testimony of my relatives from before the war. In a few years it would be too late. There will be no more people whose memory could recall the Jewish community.

I intended to go to the neighboring town of Majdan where my grandmother Sarah was born. Helena wished to come with us and directed us to the home of an old woman who lived near the main square of Majdan. Today a four-story municipality building marks the center of the square. We would learn through her friend that the only Jewish synagogue was situated on the northeast corner of the square. When the Nazis arrived in Majdan on September 12, 1939, they forced the Jewish residents to pour kerosene on the synagogue and then dance around it as it burned. Within weeks the Majdan Jews were sent to the ghetto in the city of Rzeszow. Most of them would later be shot in the nearby Glogow forest or gassed at the extermination camp at Belzec. Thus Majdan became one of the first towns known as "Judenrein," free of Jews. Hitler sent a personal letter to the local Nazi operator, Twardon, commemorating this perverse achievement.

Today nothing remains to commemorate the Jewish community of Majdan, with one exception. Buried deep in a nearby forest, approximately two kilometers southeast of the square is the remains of the Jewish cemetery of Majdan. I had with me a 1920s map of the town indicating the cemeteryís location, and even with this map it took us well into the night to find the location of this cemetery. Even Helenaís friend who had lived in Majdan did not know if and where the cemetery remained. We found it only by driving across a field on a bikepath that at one time was a likely road for horse-drawn carts but now was largely covered by brush.

The cemetery wall was broken. At one time, the cemetery contained hundreds of tombstones, now only three remain. Through a variety of sources, we were told that the tombstones and even part of the cemetery wall were removed and used as building material for the foundation of the Majdan municipal building. I had brought a roll of poster-paper and took a charcoal rubbing of the face of one of the tombstones there and later of one in Tarnow. When I returned I framed both of them and they now hang on my wall. Each time I look at them I am awestruck by the possibility that the art on my wall may be the tombstone of a distant relative dating back hundreds of years.

III. Auschwitz:Two days after my visit to Kolbuszowa I visited Oswiecim, better known by the German name Auschwitz. My experience there, like it is for most who visit, is worth an entire story. There was one tie however, to my grandmotherís shtetl. One of the barracks in the concentration camp has been converted into a repository for records on the victims of the Holocaust. When I first arrived I passed through the main gate with the cynical inscription "Arbeit macht frei" -- work brings freedom -- and headed for the repository. There, I gave the archivist the name of my family and the shtetls from which they came. After a twenty-minute search she showed me a large Yizkor book of sorts, with the alphabetized names of the victims of Auschwitz.

In this book I found indexed a distant relative of mine, Pinkas Bienenstock. In another room they provided me a copy of his death certificate which, like almost all those at Auschwitz, was signed by the Nazi SS in the first few years of operation of the camp. After murdering individual Jews they would then complete a false reason for death and send it to their families to cover up the crimes being committed. The document showed that Pinkas was born in Kolbuszowa, and, at the age of fifty-four, died on May 27, 1942. The "reason" for death was "Gehirnschlag" Ė stroke-- and it was signed by Quakernack. I would learn in the visitor center bookstore that Walter Quakernack was one of the cruelest SS guards at Auschwitz who would enjoy systematically shooting the prisoners as he explained to them that there were "more of our people dying at the front."

IV. Tarnow:The day after visiting Kolbuszowa-Majdan researching my grandmotherís roots, we drove sixty kilometers southeast to the city of Tarnow, where the Huttners once lived. Max Huttnerís immigration-boat record indicated that he was born in a place called Lichwin.

After a careful search of local Polish roadmaps I found Lichwin, located fifteen kilometers south of Tarnow. While Tarnow is a city of 200,000 people, I discovered that Lichwin is a farming village with a population of less than two hundred. Two older villagers with whom we spoke had never met an English-speaking person. While they had lived in Lichwin their entire life they had never heard of any Jews living in this village and knew of no Jewish cemetery in the vicinity. As the Huttners were dairymen, it made sense to me that they may have raised cows in this rural countryside before heading to the city of Tarnow to sell milk.

We then drove to Tarnow and visited the city archives. The three archivists carefully reviewed my letter of permission to search the records which I had received in advance by writing the Polish government. There, I searched the birth and death records of Tarnow from 1800 to WWII. The Jewish records, like those in Krakow and elsewhere in Poland, are kept in entirely separate volumes from the non-Jewish records. After searching entry-by-entry, I came across the oldest record of a Huttner that any of my family has known. It was an 1842 birth record of Meir, son of a Chaim Huttner, who, the record indicated, was a milkman in the outskirts of Tarnow. I was able to make a copy of this record and now have sent copies to my family.

Finally, I explored the old Jewish neighborhood of Tarnow which was once a community of 25,000 Jews. There were two great synagogues in Tarnow. Both were destroyed in November, 1939. Today, only the bimah of the Old Synagogue remains. I visited a few of the sites where the Jews of Tarnow met their fate. Some were shot in the square located in the Jewish ghetto, others in the Jewish cemetery, and about 6,000 were executed in a nearby forest near Zbylitowska Gora about six kilometers from town. When I visited this forest it was the same week to the date, fifty-seven years after the mass graves were filled. It was most placid: only the sound of birds chirping and the breeze blowing over the dense green vegetation and a few memorial plaques mark the spot where the bodies still remain just a foot or two under the ground on which I walked.

Perhaps even more disturbing was walking through the former Jewish neighborhood in Tarnow. Today life goes on, people walk to and from work, kids play in the street, and on the surface nothing is unordinary from any other European town. But upon closer observation, signs of a community, now destroyed and largely forgotten remain: a balneological center which was once the mikvah, the newly replaced gate to the cemetery--the original was shipped to the Holocaust Museum; and a solid silver menorah in an antique store purchased from a local resident who obtained it from the original owners prior to their deportation. The most subtle was an old doorframe of a home now occupied by Poles. When I looked closely I could still observe the nails in the wall and the indent from where the mezuzah was removed.

My experiences described were only three of my eight-day visit to Poland. Although the visit was morbid at times, the opportunity to return to Shalom Park and share pictures with my grandmother Sarah of a place she had not seen since her early childhood, was most rewarding. In many ways Poland is pleasant, the people are friendly, and the days of the Iron Curtain, primitive technology, and gray images of an oppressed working class, were left behind years ago. This visit added many of the missing pieces of the puzzle in developing a fuller image of my familyís history. Some pieces of my family history may never be found, however, I hope this article encourages others to explore their family history, and, if possible, have the opportunity to search for their own roots into a community rich with history.

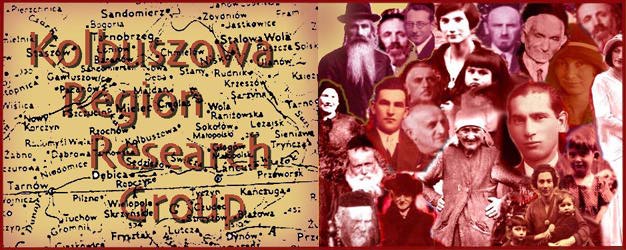

© Copyright 2017 Kolbuszowa Region Research Group. All rights reserved.