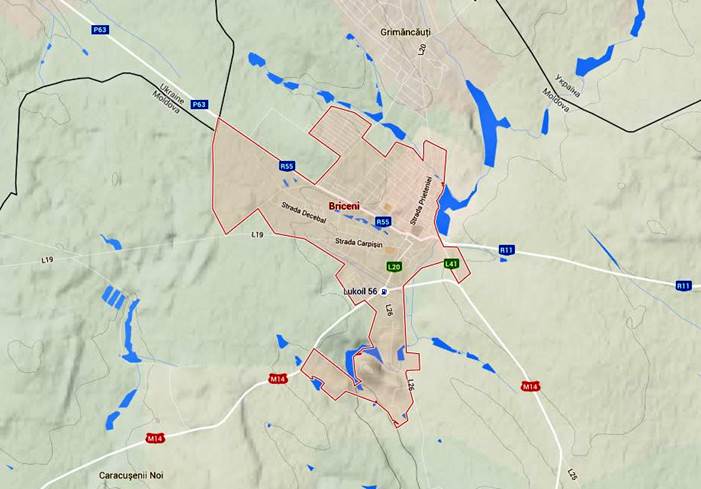

BRICENI, MOLDOVA

Alternate

names: Brichany [Rus], Briceni [Rom], Britshan

[Yid], Bryczany

[Pol], Bricheni,

Briceni-T rg (market), Bricheni

Targ (market), Briceni Sat

(village), Bricheni Sat (village), Berchan, Brichon, Britshani,

Russian: Бричаны. Moldovian: Бричень. בריטשאן-Yiddish.

There are two locations in northern Bessarabia with the same name. The first Brichany, the city or market town , is 124.1 miles NW of Chisinau, 17 miles NW of Edineţ, (Yedintsy), and 33 miles W of Mohyliv-Podilskyy. Its location is 48 22 N 27 06 E. This town was predominantly Jewish.

The second Brichany/Briceni, a village, was at 48 22 N 27 42 E, 108 miles NNW of Chisinau on the NE border of Moldova. This village was predominantly Ukrainian. In 1930 there were 63 Jews out of a total population of 3,160.1

History

18th century Moldovan state under Turkish rule

1812 Eastern half of Moldova (Bessarabia) was ceded to Russia

1877 Plague strikes the area

1882 Severe Drought

1918 Romania took control

1940 Romania forced to cede Bessarabia to the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (U.S.S.R.)

1941 Romania attempted to regain Bessarabia by joining with Germany.

1944 Soviets reoccupied Bessarabia

1991 Moldova declared independence from Soviet Union

POPULATION

1760

Jews first settled there.

1788 Austrian

military administration recorded 56 households in Brichany

1817 there were 137 Jewish families living in the town; another 47 had previously left the

settlement when it was partly destroyed by fire.

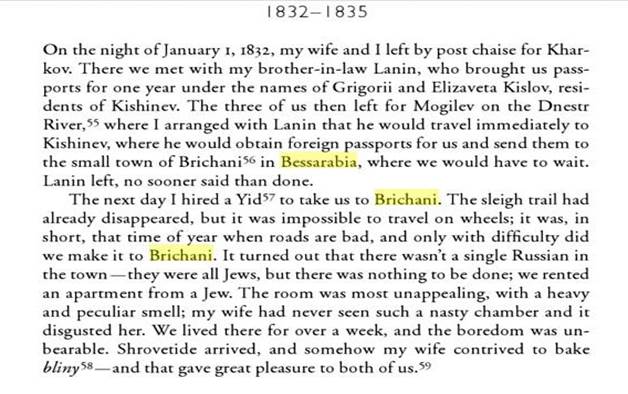

1832 only Jews lived in the village*

The community increased in the first half

of the 19th century, and by the middle of the 19th century it was among

the largest in the region.

1848

Middle Class census lists 599

families with 5,837 records

1859

census lists 350 families

1897

there were 7,184 Jews in Brichany (96.5% of the total

population)

1930 According to the official census figures, the Jewish population numbered 5,354 (95.2% of

the total).

1940 Before World War II many Jews from surrounding areas concentrated in Brichany, and by

1940 it had a Jewish population of about 10,000.

2004 According to the census, 8,765 people were living in Briceni, of which only 52 were Jews.

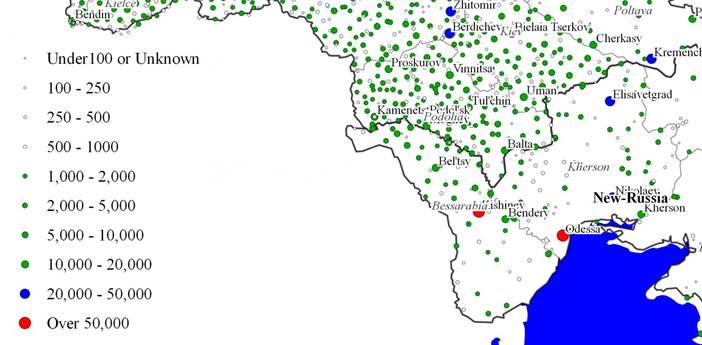

Jewish Communities in the Pale of Settlement 1897

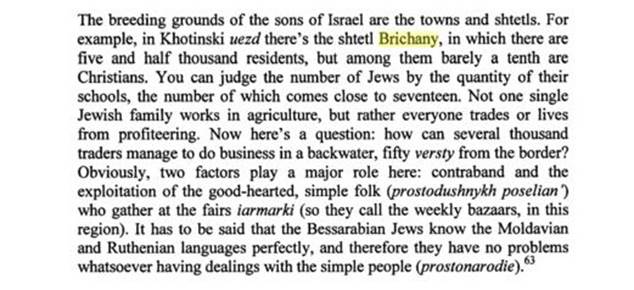

*Examples of 19th Century Anti-Semitism in Writing

Excerpt from the autobiography of Nikolai Shipov, a serf born in 1802 in the province of Nizhnii Novograd. It was published in 1881 in Russkaia Starina, a Russian journal of historical and memoir material. It was reprinted in 1933.

Below, Jews are presented as an exploiting presence.

Excerpt from Travels in Southern Russia written in 1863 by Afanas ev-Chuzbinskii

Physical Environment

The climate is temperate with an average temperature of 46.4 F. In summer, the average temperature is 67.1 F and 22.1 F in winter. It receives rainfall of 23.6 25.6 inches on average in the district but sometimes as much as 31.5 inches. This part of Moldova is wetter than in the south.

The Bessarabian hills were once heavily forested; but reckless exploitation under the Russian regime left the country almost treeless, and the war completed the devastation, since no other fuel was available. 2 In 1926 the Roumanian Forestry Department set to work to improve conditions, with Transylvania as a model. The district of Hotin had about 20% of its area under forest. Today, forests occupy 10.0% of the district. There are: English oak, maple, birch and mugwort.

Fauna of the district is typical of European forest steppe, characterized by: hare, hedgehog, squirrel, fox, stone marten, and weasel. To a lesser extent can be found deer, wild boar, and badger, and rarely elk can be seen. The common birds are: skylark, blackbird, quail, stork, and starling, and to a lesser extent partridges and pheasant.

Brichany is located between the two large rivers, Dniester to the north and east, and Prut to the west and south. However, there are many smaller rivers and streams formed from the run-off of the hilly terrain. The city is close to what is currently called the Lopatinka River, but the shores were flat and the city had room to grow. While the general area is not flat, it is also not too hilly. There was little danger of rockslides, but the river would overflow its banks in the spring . Another river, the Dadeles, also bordered the town, but cannot be found as a named river today. The rivers allowed for ample drinking water as well as power for flour mills.

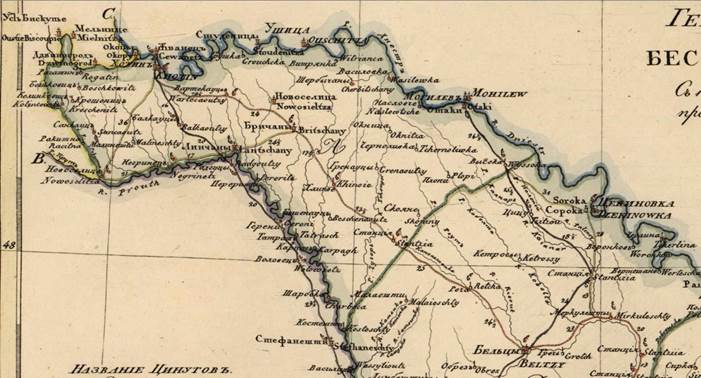

Although Brichany did not have a train station or a location close to one of the two large rivers, its central location helped give it a high social, economic, and cultural standing in northern Bessa- rabia. This 1821 postal map shows that a major road with postal route went through the town.

1821 Postal Map in Russian and French

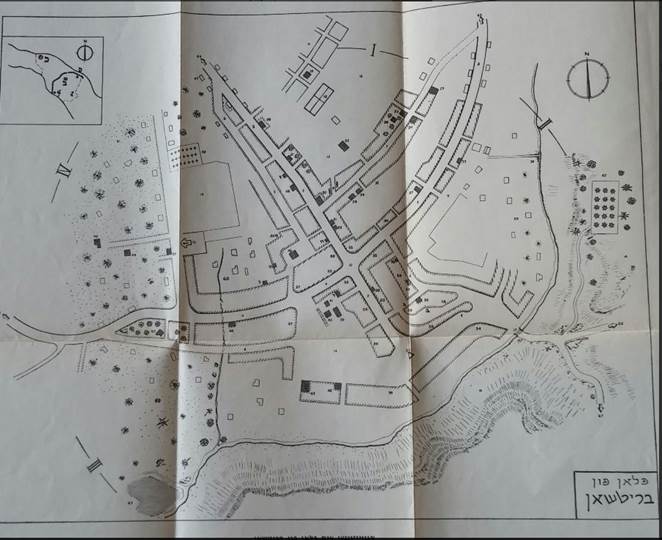

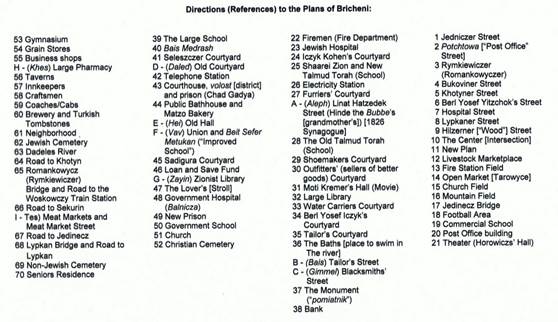

The city was divided into quadrants by two main streets; Pocztowa Street ran from east to west and Rymkiewiczer-Bad (bath) Street ran from north to south. Poctztowa Street led out of the city to Jednicz and Sekuryani in one direction, and to Hotin in the other direction. Rymkiewiczer-Bad Street went to Waskocz for the train station in one direction, and to Lypkany in the other. The streets were generally flat and only slightly curved.

The Christians lived in one quarter where the neighborhood spread out. Also located in this quarter was the hospital, prison, two classical schools, the gymnasium, the church, and the non-Jewish cemetery. The rest of the official institutions that were connected to commerce and especially to the wider population, were found in the Jewish section: postal service, telephone station, and Wolost , administrative division, for taxes and justice.

The purely Jewish institutions (Houses of Study, hospitals, schools, theater), were located mainly in the center of the town, but also in several more distant points in the Jewish district. The center of town was also the main area of commerce. However, the grain trade was at the beginning of Pocztowa Street, near the Yedinitz bridge. Craftsmen were mostly located on back streets, especially in the second quarter. Inns and taverns were located on the left side of Torhowyce Street.

There were four open places within the city; the fire department meadow in Quarter 1, the Torhowycza or bargain center in Quarter 3, the church meadow in Quarter 4, and a large open area on the right side of the river, outside of the city this was the bridge meadow that served mainly the population from the closer edge of the city.

Cemetery

The Jewish cemetery is across the river on the highest tip of the hill. It could be seen from all parts of Brichany, and the sun s setting light from the west reflected off the black tombstones and mausoleums in the east.

The cemetery is currently surrounded by a broken wall with no gate. It is a 10.000 sq. meter site with a new and old section. There are about 5,000 gravestones consisting of rough stones and boulders, flat shaped stones, finely smoothed and inscribed stones, flat stones with carved relief decoration, double tombstones, and sculpted monuments. The oldest dates from the 19th century. Some are tumbled or broken. About 2,500 gravestones are legible. Their photos will soon be available on JOWBR due to funds raised through Bessarabia Sig.

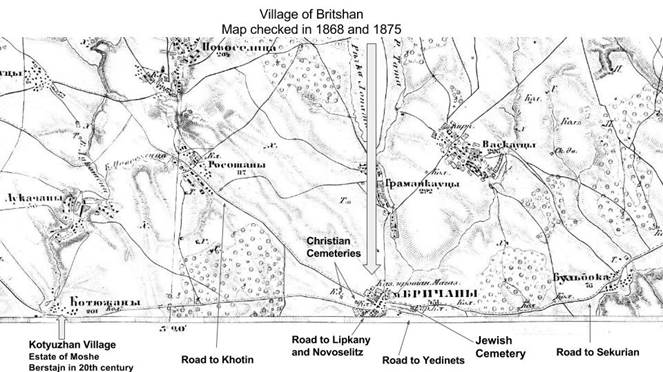

Brichany - XXXVIII-22 - The Third Military Mapping Survey of the Austro-Hungarian Army 1916

Brichany in map above is about 2.5 square miles

Map Insert from Britshan Memorial Book

INSTITUTIONS

Synagogues

1826 Shul - It was built from stone, large and tall. At the entrance to the shul, there was a balcony; then you entered the corridor, from which on both sides there were two small synagogues. You descended five steps and entered a large temple. An exceptional awe befell you the height, the size, the elegance!

The dome was painted as the sky, and the brilliant moon and glittering stars were fitted right in. Around the walls, the zodiacs. On the left wall, at the entrance, there was a large, round matzo hanging as an indication of an eruv. [The matzo is part of the ceremony conducted to enable Jews to carry items on the Shabbath, an act that is prohibited by the Torah].

The congregants of the shul comprised mainly of working men. Practically no wealthy men prayed there. 3

In 1897 there were seven synagogues. Before the Shoah there were 14 synagogues. Each group of craftsmen had their own shul - a tailor s, a furrier s, a water porter s, etc.

Rabbi and Cantor Chaim Millman, son of Rabbi Itzchock Millman, was born in Brichany in 1893. After emigrating to the United States, he sang in the great synagogues of New York City, Boston Philadelphia, Newark, Cleveland, Chicago, as well as in Montreal and Toronto, Canada. 4

Jewish Hospital

The Jewish hospital was founded in 1885. It was run by the Association for the Needy which also administered the matzo factory and the old Hebrew school. Monies to support the hospital came from association dues, donations, and inheritance bequests, but the majority of the money came from taksa , the lease paid by the butcher. The Czarist regime gave no money for the support of Jewish institutions. The taksa was created for this purpose. Whoever received the three year lease from the government to be the supplier of kosher meat was required to pay the government treasury annually, to pay to maintain the synagogue, Hebrew School, Rabbi, and shochet, and pay toward the support of philanthropic institutions.

It is believed that the plot of land for the hospital was donated by Yosef Zilber and his wife Sarah. They also gave money to build the modern matzo factory, and the proceeds from the factory also supported the hospital.

Under Romanian rule, many in Brichany became impoverished. The activists in the city created a Kehila, or Jewish community, to make institutions better run and to provide for the increased needs of the growing poor. The hospital and other institutions were transferred to its administration, and the Association for the Needy was disbanded.

Home for the Aged

To meet the needs of the homeless elderly, Henia Bershstein initiated a committee to establish a Home for the Aged. A year later, in 1918, Dr. Shvartz died and left his home to be used for this purpose. After renovations and remodelling the home was opened for thirty elderly men and women.

Libraries

The first library was established in the 1890 s and was housed in the home of Shlomo Veinshtein. Avraham Kleinman was the first director. After his passing in 1904, the library was moved to the home of Avraham Goldgal. All these men were active in the group Hohevai Zion . When the interest in Zionism decreased, the usage of the library decreased and the library closed. Whatever good books had not been lost or kept by the readers, fewer than 50, were transferred to the public library.

The public library opened in the beginning of the 20th century. In addition to the books in Hebrew transferred from the closed library, there were 1800 books in Russian and and a few in Yiddish written by Mordechai Spektor, Yaakov Dinzon, and Meshel Shemer. By the time the library was closed by the Romanians because they suspected the leaders were Bolsheviks, the library contained nearly 7000 books, among them 180 in Hebrew and about 300 in Yiddish.

In the early years of the public library, no public body supervised its activities. It was officially owned and maintained by the society Support of the Poor . In reality, leftists headed by Katya Ginzburg ran the library. In later years there was a struggle when Zionists tried to have an influence. After their demands to increase the budget for new Hebrew and Yiddish books were denied, a new Zionist library was opened in Brichany. This library was first housed in homes and later in the New Talmud Torah. It had about 1800 books. It was these Zionists who fought for the release of the public Librarian, W. Kizhner, who had been arrested by the Romanian authorities and for the reopening of the public library.

In addition to the libraries, there were several short-lived reading rooms where people could gather to read newspapers and literature and to enter into lively debates. On of these was a secret reading room during World War I.

Schools

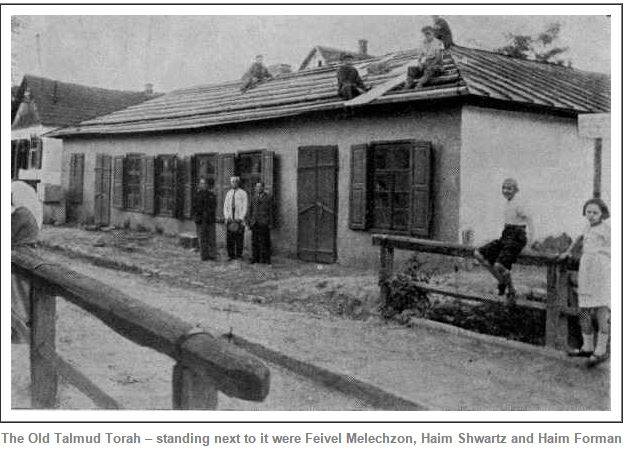

The first school was established in 1826 by the chief Rabbi R Yitzhak-Meir. The Talmud Torah was located on a small street by the name of Linat Hatzedek and was in existence for 100 years. In the 20th century is was attended by poor children who learned only basic reading and prayer. The head of the school, Haim Schwartz, saw the school only as charity work and was not interested in modernizing the studies.

The Zionists initiated construction of a new Talmud Torah school in 1920. After many setbacks, the school opened in 1923 with 150 children registered.The curriculum included both Jewish and secular studies. There were several failed attempts to merge the new and old Torah Talmud schools.

There were also several short-lived schools including a Russian-Hebrew school initiated by the Society of Tradesman in 1910, a Hebrew kindergarten in 1925, a Yiddish school, and others.

By the first decade of the 20th century, most children went to school, even the poor. They wanted a better future for themselves than following in their father s trades. Some went to Kiev, Odessa, or Kamenitz-Podolsky for high school, but many were not accepted and had to study from home. The heavy expense for school was a sacrifice for many parents. Some youth were able to find employment as tutors, but others were fortunate to have expenses paid by a man of the Russian intelligentsia, Kazimir, who was the owner of the largest estates in the area and also the nearby village of Vaskautzi. He established a Stipend Fund so that anyone, regardless of religion or race, could afford to attend school. When he died in 1912, many Jews from the surrounding area went to his funeral including a cantor and choir from Mogilev-Podolski. Many Christian attendees showed their displeasure by leaving the funeral.

Some of the schools within Brichany included a short-lived vocational school for girls run by Jewish women to teach sewing and knitting, a school of commerce run by anti-Semitic teachers, and a gymnasia founded in 1920 by a Jewish woman who had come from Hotin, Roza Solomonova Diker. The strong high school education received at the Gymnasia allowed students to go abroad and receive degrees in engineering, medicine, law, etc. There was also a Hebrew school, but due to the amount of time spent learning Hebrew, the students there were not prepared to study for higher degrees.

Theater

Yiddish travelling theater groups

frequently visited Brichany, including troupes from

Warsaw and Vienna. Groups from Russia and Ukraine also visited. Local youth and

amateurs performed plays by Shalom Aleichem, Pinsky, Hirshbein,

and others. Brichany also had mock trials on various

literary topics. Some of these would last 6-7 hours and listeners would

excitedly await the court decision . For days after there would be disputes

about the outcome of the trial , and librarians often found the demand for

these books increased. Sometimes people were moved to the extreme. In the

trial of Motke the Thief, S. Kilimnik

the clockmaker was appointed one of the judges.

He was most influenced by the words of the defending attorney and voted for the

acquittal of the accused . The next day he regretted his decision and became

very disturbed and emotional and could not calm himself. He said, What did I

do? If Motke had broken into my store and stolen all

my merchandise, would I then have found him innocent? 5

Hershl (Harry) Kaufman, born Feyner, 1880-1959

|

Hershl Feyner was born to well-to-do parents in Brichany. He came to New York for his |

first sister's wedding, and remained in the United States. After two years of trying various trades, he became a fur worker and took his brother-in-law's family name "Kaufman".

He wrote the following melodramas and scenes for the Yiddish theatre of America: "Der preyz far reykhtum", "Erlekhe froyen", "Heylike nshmus", "A harts fun shteyn", "Der yidisher shtern".

He was Protocol leader in the Yiddish vaudeville union for four years, Protocol Secretary in the Actors Union for thirty years, and later he held the same office in the Yiddish Theatrical Alliance.

Food

A description of the food eaten by the city dwellers of Brichany during good times can be extrapolated from the list of a nearby Jewish villager from Kotyuzhan. While the family worked in agriculture and could provide for itself perhaps a wider array of foodstuffs, their foods tell us what was available and eaten in the area.

In the large barn, there were always

many different provisions: wheat flour, cornmeal, maize, and all kinds of oats.

In the cellar, there were large barrels of sauerkraut, sour pickles,

watermelons, peppers, and tomatoes; barrels of sour apples, jars with all kinds

of preserves from sour cherries, cherries, gooseberries, raspberries, and other

fruit; roasted prune jam and apples, from plums, from pears, etc. Aside from

that, there were jugs of milk, with sour cream, butter, all kinds of pressed

cheeses from cows and goats: whey cheese, kashkaval

cheese, and Urda cheese [similar to ricotta]; a small

barrel of herring and dried fish. In the winter, the cellar was filled with

potatoes, onions, garlic, beets, and other products, and a few bottles of wisniak [sweet cherry liquor]. In the attic was roasted

chicken and good fat, and smoked meat was hanging, also pastrami, and thin,

filled kishke

[intestine]. 6

OCCUPATIONS

It was estimated by a former resident, Yakov Amitzur-Steinhaus, that 40% of Jews in Brichany dealt in commerce, 35% were craftsmen, and the remainder were agents, middleman, professionals, and religious ministrants, or those with no livelihood.

There were about 20 large villages around Brichany, and the Christian farmers would bring their produce to market in Brichany. Their wives would also bring things to sell that they had made over the winter. After the Jews bought produce from the Christian farmers, the farmers would buy food, clothes, shoes, tools and other products from the Jewish craftsmen and shopkeepers. There were also restaurants and bars whose main income was from the neighboring farmers. Some Brichany craftsmen travelled to other large towns in the area and as far as Lipkani, Skorani, and Yedinitz to sell their crafts. Relative to other towns, Brichany was in a good economic situation.

In 1898 there were 972 Jewish artisans, most of whom were furriers who produced and exported up to 25,000 fur overcoats and caps per year. 25 families were dedicated to gardening and to producing tobacco. About 700 Jews were day laborers, earning 10 30 kopeck per day.

Between the world wars Jews traded in cattle, hides, and farm produce. Fruits, tobacco, and sugar beets were major crops. A few Jews leased land from estate owners and hired workers from among the farmers to work this leased land. When under Romanian rule, some of these lessees bought the land as Jews were no longer prohibited from acquiring land. The very wealthy Bershstein family had special privileges even under the Czar s rule to own property. Among their holdings was a large flour mill in Sankautzi. This mill and another owned by Yosef Babanchik in the nearby village of Chaplautzi were among the largest in Bessarabia. They supplied flour to large and small cities in Bessarabia and Ukraine. Flour was the major industry of Bessarabia in the 1920s. There were also two oil factories and a winery.

In 1924, 125 Jews were engaged in agriculture on 641 hectares (approx. 1,600 acres) of land, most of it (500 hectares) held on lease. The 1924-1925 Bessarabia Business Directory7 listed people with the following occupations:

4 carpenter 1 medical doctor

8 fabric store 1 notary

10 grain trader 1 pasta maker

23 grocer 1 pharmacy

9 haberdashery 2 shoe maker/cobbler

9 land owner 3 tailor

1 mayor 2 teacher

Holocaust Period (1939-1945)

In June 1940, when the city was annexed by the U.S.S.R., Jewish property and community buildings were confiscated and only the synagogue was saved because it was used as a granary. People were left without a source of livelihood and many starved.

Some 80 Jews, mainly community leaders, were exiled to Siberia and others escaped to other towns. This left the community with no leadership to organize resistance.

July 22, 1941 Romanian and German troops passed through Brichany and murdered many Jews.

Jews from the neighboring towns of Lipkany and Sekiryany were brought to Brichany.

July 25, 1941 the Lipkani Jews were forced to march to Edinet.

July 27, 1941 the Sekiryany Jews were forced to leave

July 28, 1941 all Jews of Brichany and surrounding villages were forced to march toward Sekiryani. The first person to die was David, son of Rabbi Shalom, who collapsed under the weight of the sack of books he was carrying. After passing through Sekiryani they were attacked by a gang of boys who stole their possessions. Finally they were allowed to rest for a few hours. The next morning they were sent across the Dniester by way of a temporary bridge. Outside the village of Kozolov they were forced to dig pits into which posts were placed and then surrounded with barbed wire. After three days without food or water, the Jews gathered money and gold to bribe the Roumanian officer in charge. He permitted them to go in groups of up to a thousand through nearby villages.

August 4, 1941 they arrived in Mogilev, the Germans "selected" the old people and forced the younger ones to dig graves for them.

From Mogilev the rest were turned back to Ataki in Bessarabia and then on to Sekiryany. Hundreds died en route. For a month they stayed in the ghetto, only to be deported again to Transnistria where all the young Jews were murdered in a forest near Soroca.

Only 1,000 Jews returned to Brichany at the end of the war.

In the years 1944 46 another 1,500 Jews from Bukovina returned from Transnistria and reestablished the Brichany community while they were waiting for permission to return to their homes.

Wherever possible, they boarded up doors and windows, and squeezed entire families into one room; they dragged boards from fences, and assembled some sort of bedding. This was all done without fear of the new government that was very involved with the activities of the returnees. I and Buzhi Rojter almost paid with our freedom for a bed that we took from an abandoned house, when an NKVD [Russian: People s Commissariat for Internal Affairs, law enforcement agency of the Soviet Union] commandant told us that he had left this bed for himself.

After the so-called organizing, there began a search [for means] to earn some money, to sustain life. And now winter was approaching, the houses were absolutely not suited. Some of the local residents offered to take on government jobs or work in labor cooperatives. Although the salaries could not cover even thirty percent of the needs of the poor, nonetheless a shield of armor against poverty. It was more difficult for those who could find no work especially for the Bukovina, since they didn t hire any foreigners. As a result, illegal business began. At night they bribed whoever they could, and merchants would go to Dniester, also to Czernowycz, and bring merchandise that was needed, and the peasants themselves needed them. Everyone well knew what was going on, and there were times when they fell in [were caught], but there was no choice

We lived through difficult moments, when, because of their specific situation, the Bukoviner involvement in the black market was particularly outstanding. They also created lively social activities: they organized their own elections, amassed help for the needy. Reports about their activity began to fly to the higher ups. It didn t take too long, and just on Rosh Hashanah an order was given by the commandant of the NKVD from Chisinau [Kishinev], that they [the illegal merchants] be assembled and sent off to Siberia. It s understandable what terror and chaos this decree created, but they did not lose themselves; they collected a large sum of money, valuable things, ran off to Chisinau and bemoaned their tragedy. 8

And in passing, the Brichany priest should also be mentioned for good things, that on the day of the evacuation, he went to the shul, removed the Torah scrolls, and took them to his home. He left together with the Romanians, and we found the scrolls in the attic, and collected a few religious books that were strewn about the abandoned houses. This is how a little bit of Jewish life concentrated itself in the shul. Daily, especially on Shabbath and on Yom Tov [Jewish holidays], there were religious services and traditional religious customs. 9

That was just about how the thoughts were of the majority of the returnees. And at the first opportunity, when the Bukoviner received permission to return to their homes, many Brichener, also of those who already lived in Czernowycz, using any means and methods possible, went along with them.

When the Bukoviner left, we who remained felt empty how hollow our lives were, how great was the destruction. The few elderly people who were able to come to shul, did not have anyone to lead the prayers for them, nor anyone who could read from the Torah scrolls. Chaim Shmuel Shuster argued that before an entire community of Jews will sin, he alone will take the sin upon himself. He took out his shoemaker s knife, and became the schochet [ritual slaughterer]. There was no one to take care of community issues because everyone was preoccupied with earning money for that small piece of bread, and was tired of getting up at night to stand in line for that sticky bread, depressed with fear, not knowing what tomorrow would bring.

That s how the new Brichany looked in the year 1945, when I left it. My heart was ripped apart, looking at those miserable ones who could not move from their spot. When they started to whisper that I was going to leave, Moshe Trachtenbroit said to me: With your leaving, the last Jew who knows some Jewish words [about Jewish life] and reminds us that we are Jews, is leaving as well. 10

According to the narrations of Dena Moshe Karlon s wife who left Brichany in 1956, Jews left the city at a quick pace. Whoever had even the smallest opportunity ran to Czernowycz, with the hope from there to go farther Few remained, those who did not have even the most minimal physical or material opportunities to move from their place; beaten, poor people, without any outlooks or hopes; as if intentionally staying behind to watch the oncoming destruction of the city. 11

Before abandoning Brichany, the Jews of the town took down the large, old shul built in 1826. Particularly moving, was her story about the destruction of the large shul down to the ground. The beautiful shul whose very soul is bound up in the memory of each Brichany Jew, that even in the years of the world s demons was respected by the Nazis, was gruesomely destroyed after the so-called liberation.

When they brought Christian workers to perform the devastation, they categorically refused. The son-in-law of the cantor Efraim Zalcman took the holy mission upon himself. He brought workers from far away. When the bulldozer bit into the thick walls of the shul, the noise, like a long thunder, was heard across the entire city. Jews cried quietly for the destruction and Christians ran from all over to watch the evil wonder. Afterwards, they said that when the walls were torn down, they heard cries and moans coming from the shul. 12

Landsmanschaften

Israel, Britchaner Bessarabian Relief

Association

London, Star of

Moses and Britchauer Friendly Benefit Society

Chicago, Brichonner Bessarabier

Association

has a burial section in Menorah Gardens Cemetery

New York:

Year Inc. Doc. # at YIVO

First Britschaner Benevolent Association 1898 380

First Independent Brichaner Society 1900 360

First Independent Benefit Association of Brichan 1901 499

Erster Independent Brichaner Unterstutzungs Verein 1901 499

First Brichaner Congregation 1903 793

First Brichaner Men of Truth 1903 805

Brichoner Young Friends Benevolent and Educational Club 1911 1447

Independent Britchoner Bessarabian Benevolent Association 1911 4820

has a burial section at Montefiore Cemetery, Springfield Gardens,

New York, Blocks 89 and 91, Gate 32/NE

Britchaner Young Men and Young Ladies Benevolent Association 1914 5504

Britzaner-Bessarabier Progressive Young Folks 1915 3568

Briceni 1978

|

Briceni Today Area: 3.861 mi

Sources: 2Bessarabia - Russia and Roumania on the Black Sea, Charles Upson Clark, Dodd, Mead & Company, New York, 1927 Four Russian Serf Narratives, John MacKay, Univ of Wisconsin Press, 2009Jewish Genealogical Society of New York http://www.jgsny.org/index.php/ajhs-incorporation-data-menu 3,5,6,8,9,10,11,12Memorial Book: Brichany: Its Jewry in the first half of our century, Edited by Yaakov Amizur, Former residents of Brichany, Tel Aviv, Israel 1964 http://www.jewishgen.org/Yizkor/Bessarabia01/Bessarabia01.html |

Red Kasrilevke: Ethnographies of Economic Transformation in the Soviet Shtetl, 1917--1939, Deborah Hope Yellen, ProQuest, 2007, p58

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Briceni_District

7http://www.jewishgen.org/Bessarabia/files/projects/5BusinessDirectory/Khotin-district.htm

http://www.jewishvirtuallibrary.org/jsource/judaica/ejud_0002_0004_0_03535.html

http://www.museumoffamilyhistory.com/yt/lex/K/kaufman-hershl.htm

4https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=TOegoNcVLAw

Maps

Bessarabia gubernia 1821 (Russian, French)

Brichany - XXXVIII-22 - The Third Military Mapping Survey of the Austro-Hungarian Army 1916

NO LONGER AVAILABLE http://easteurotopo.org/images/s84_western_Russia/XXXVIII-22_s84_Brichany_LC_1916.jpg

Britschane from Neueste Karte von Moldau Walachei Bessarabien und Krim (1789) C. Schutz

https://polona.pl/item/24560193/0/

General Map of Bessarabia: Showing

Postal and Major Roads, Stations and the Distance in Versts between Them (1821)

Distances are shown in versts, a

Russian measure, now no longer used, equal to 1.07 kilometers.

https://www.wdl.org/en/item/664/view/1/1/

Google Earth and Topo

Jewish Communities in the Pale of Settlement 1897

http://yannayspitzer.net/2012/07/22/a-new-map-of-jewish-communities-in-the-russian-empire/

Military-Topographical Maps of Russian Empire created in 1846-1863

26-5 Khotin Ataki (near Khotin) Brichany

Railways near Briceni - Eisenbahn Karte von Russland (1900) G.F. Raab

NO LONGER AVAILABLE http://easteurotopo.org/images/thematic%20maps/Rail%20Maps%20of%20European%20Russia/1900_Eisenbahn-Karte-Russ.html

Miscellaneous

Other towns in Moldova where Jews were numerous before WWII are Ataki (Otaci, Atachi),

Beltsy (Belti), Faleshty (Falesti), Kalarash (Calarasi), and Soroki (Soroca).

Bessarabia Special Interest Group (SIG) webpage: https://www.jewishgen.org/Bessarabia

Romania/Moldova Special Interest Group (SIG) webpage: https://www.jewishgen.org/RomSIG/

Hungarian Special Interest Group (SIG) webpage: https://www.jewishgen.org/Hungary/

Ukraine Special Interest Group (SIG) website: https://www.jewishgen.org/Ukraine/

Introduction and History of the Jews of Moldova: http://jewishmemory.md/en/

Some of the material was prepared by Roberta Jaffer for the Bessarabia Special Interest Group meeting of February 28, 1916, under the leadership of Yefim Kogan, in Newton, Massachusetts.

Kehilalinks Directory | JewishGen Home page | Top of Page

Briceni Kehila Link Webpage Coordinated by Barbie Schneider Moskowitz Bmosk2@gmail.com

Webpage was created and maintained by Barbara Cholfin Johnson until 2012.

Updated RLB:Jan 2024

Copyright 1998-1999