|

Panemunė (Aukštoji Panemunė, Lithuania) |

Jewish Settlement in Panemune

By

Rabbi Jeffrey A. Marx

January,

2022

Demography

Jewish settlement in Panemune is documented in the 1790s, though it is

highly likely that Jews lived there for some time before that.[1]

In the late 1790s, there were 51 Jewish households there, accounting

for more than 200 of Panemune’s 490 inhabitants.[2]

In 1799/1800, 393 of Panemune’s 844 inhabitants were Jews.[3]

In the first half of the 19th Century, the Jewish population of Panemune

grew, perhaps due to Czar Nicholas I's (1825-1855) restrictions that Jews

could only build in the suburbs of cities.[4]

Vital records for Panemune in the 1820s show over 125 households

there, and over 165 households in the 1830s, though the actual number would

have been higher.[5]

Between 1843 and 1845, 231 Jewish households were found in Panemune,

consisting of 1,219 individuals.[6]

Though during the second half of the 19th Century, the Jewish population

increased in Lithuanian urban areas, the population of Panemune seems to

have decreased, perhaps due to emigration[7]

or that, from 1827 through 1874, Jewish males in Panemune were subject to

military service.[8]

In the 1870s there were at least 130 Jewish families living there.[9]

In 1897, there were 775 Jews living in Panemune, perhaps constituting

155 households.[10]

During WWI, when Germany declared war on Russia (July, 1914) and invaded

Lithuania, moving eastward towards Russia, the Russian High Command and

General Staff blamed their losses on German spies and traitorous Jews.

By the spring of 1915, the Russian High Command decided to expell the

Jewish communities in Suwalk and Kaunas Gubernias into the Russian interior

rather than risk them aiding the enemy.[11]

The Jews of Panemune were among those

expelled, probably between May 3d-5th, 1915.[12]

Some returned when the Germans captured Kovno on 8/5/1915.[13]

Many, though probably not all, returned at the end of the war in

1918.[14]

In 1921 there were 18 Jewish households in Panemune, consisting of 102

individuals.[15]

In 1923 there were 387 Jews living in the town.[16]

In 1925 there were 60 households.[17]

In the early 1940s there were, approximately, 100 Jewish households,

there, consisting of more than 250 individuals.[18]

Map of Panemune in

the 1940s

The

Community

From 1623 until 1764, Panemune was in the Grodno administrative region of

the Jewish Council of Lithuania.

There was an organized Jewish community in existence by 1824.[19]

A mikvah was in existence before 1836, which was the year it burned

down.[20]

In 1842, Yecheil Eliezer Hellir was the Rabbi and Av Bet Din (Head of

the Rabbinic Court) there.[21]

Though there was an established Jewish community, some of Panemune's

Jewish affairs, by 1842, were under the control of the Kovno rabbinate.[22]

Around 1858, Panemune had a small synagogue for daily prayer and a large one

for holidays.[23]

The community had a cemetery, as well.[24]

From 1890, Binyamin Meisil was the rabbi there, followed by

Mordechai-David Henkin and Ephraim-Nisan Ma-Yafit.[25]

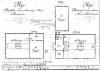

10/8/1857 Blueprint

of the Two Synagogues

Between 1911 and 1915, Jewish-owned businesses in Panemune included 19

consumer goods shops, a butcher, and 5 liquor enterprises.[26]

[1]

The 1784 Revision list of the town of Ponemune in the Kaunas

District (Feb. 12th, 1784) lists 21 heads of households

comprising 63 individuals. While it is likely that the list referred

to the inhabitants of Aukstoji Panemune, it cannot be ruled out that

they were inhabitants of Panemune Pozailis, which was 3 miles east

of Aukstoji Panemune.

[2]

Pinkas HaKehillot (Ed., Dov Levin, Poland, Vol. IV, Warsaw

and its Region, 1989, Lithuania, 1996, Yad Vashem, Jerusalem, p.

496) states that in 1792 there were 490 inhabitants of Panemune but

does not indicate how many of the 490 families were Jews. Berl Kagan

(Yidishe Shtet, Shtetlech un Dorfishe Yishuvim in Lite,

Simcha Graphic Associates, N.Y., 1991) states that in 1797, Panemune

had 490 inhabitants, mostly Jews, who lived in 51 households.

It must be kept in mind, however, that Panemune, until 1884,

was an estate that included not just the town of Panemune but

several surrounding villages.

(Jogichiszki,

Kruki, Polobi, Tyrmiany and Uruky).

Thus, demographic data for Panemune up until this date may

have included inhabitants from these nearby villages.

From 1819-1825, for example, a number of Jewish families are

recorded as coming from these tiny villages.

(See

Encyclopedia Lithuanica, "Aukstoji Panemune”;

1819-1825 Births, Ponemon-Fergissa, LVIA 1236/1/9,13,21,22,26).

[3]

Jan Wasicki, Prussian Descriptions of Polish Towns From the End

of the 18th Century Bialystok Department, Adam

Mickiewicz University, Poznan, 1964.

The high percentage of Jews among the Panemune population was

probably due to the fact that Panemune was privately owned at that

time. The inhabitants, like the majority of Lithuania’s Jews,

probably made their livelihood by, “…leasing estates, and running

hostelries, distilleries, breweries and taverns”.

(Dov Levin, The Litvaks, op. cit., p. 53).

[4]

(See Kagan, Op. Cit.)

[5]

125 family units are found in Panemune birth, marriage or death

records during the 1820s, consisting of 80 unique names. (Kaunas

Birth, Death, Marriage Records, Death Records, Panemune Frentzele).

Some of the

bearers of the 45 shared names were, no doubt, relatives, and some

may have been living in the same home.

It may, thus, be stated with certainty, that that there were

a minimum of 80 distinct families living in Panemune during the

1820s, and that the actual number was, no doubt, higher, since their

names would have been recorded only if there had been a birth,

marriage or death within a family at this time.

[6]

1843-1845 Tax Report from Jewish Community of Poniemon

Frentzela (CWW 1835, Archiwum Glowne Akt Dawnych/Central Archives of

Historical Records, Warsaw) states that there were 647 men and 572

women. In addition,

there were another 5 Jewish families on the outskirts of Panemune,

consisting of 47 individuals.

5 of the 236 families in Panemune were of the 1st class, 100

of the 4th class and 52 of the 5th class.

[7]

During the second half of the 19th Century, Jews began moving into

urban centers. Thus, in

1847, the combined Jewish population of Kaunas and Slobodka was

7,000, while by 1864 it had grown to 16,500.

By 1915, the Jewish population of Kovno had reached 40,000.

(See Yahadut

Lita, Op. Cit.).

[8]

(See 1875 Judel Bragsten application to Vistas i Riket

(Civildepartementets Konseljakt, Riksarkivet (National Archives),

Stockholm, Sweden) and Encyclopedia Judaica (Keter Publishing

house ltd, Jerusalem, Israel, 1971, "Cantonists"; Independent Suwalk

& Vicinity Benevolent Association and Relief Committee,

Jewish Community book for

Suwalk & Vicinity, Tel Aviv, New York,1989.

The law of 1827 forced Jews, ages 20-25, (though children

12-18 could be substituted) to serve in the Russian army for

twenty-five years.

Exemptions were given to craftsmen, factory workers, farmers, rabbis

and those registered in one of the three merchant guilds. The

conditions were eased, somewhat, under the reign of Alexander II, in

1856. In 1874, a general draft was instituted for all 20 year old

males. (See Dov Levin, The Litvaks, op. cit., pp. 67, 72,

73.)

[9]

Bernard Horwich, (My First Eighty Years, Argus Books,Chicago,

1939, p. 2) gave

the number of households as 100.

Birth, Marriage and Death records from Kaunas together with

the 1872 Supplement to HaMagid

(#6, Lyck, Feb. 7, 1872) show at least 130 households.

Assuming that the contributors found in the 1872 Supplement

did not constitute all the inhabitants of the town, and assuming

that not every family in Panemune might have a birth, marriage or

death from 1870-1879 and hence would not appear in vital records,

leads to the conclusion that the number of households was even

higher. It should

be noted that the birth records from 1860-1879 indicate an average

of two children per family of the families bearing children.

Though Horwich states that there were only four Christian

households in the town at this time, this seems highly unlikely.

[10]

This was out of a general population of 1,575.

(See Pinkas HaKehillot, Op. Cit., p. 496).

Approximating five to a household, would make 155 households.

(See Jewrejskaja Enciklopedia (1897?) and

Evrejskaya Entsiklopediya (St. Petersburg, 1906-1913, Vol. IX,

pp. 339-341).

[11]

See Dov Levin, Op. Cit., pp. 30, 76; Anatoli Chayesh, Op.

Cit., “The Expulsion of the Jews from Lithuania in the Spring of

1915”, LitvakSIG Online Journal, www.litvaksig.org, 2/2000.

[12]

This is when the Jews of Kovno were expleed.

(Anatoli

Chayesh, Op. Cit.)

Though there are no offical

records of Panemune Jewry among the expelled, there exist records of

75 Jewish

households representing several hundred Jews from Alexota - next to

Panemune, also directly across the river from Kovno - who were sent

either to Vilna or to Minsk.

(Galina Baranova, “More 1915 Eviction Data: Part I”,

Landsmen, Vol. 11, Nos. 1-2, July, 2001.

Data extracted from Fond #1010- Chancellery of the Suwalk i

Government, Lithuanian State Historical Archives).

In addition, there is the account of Wolf Bregstein (letter

to Jeffrey A. Marx, 4/18/1987) in which he stated that he, his

sister, Mary and his mother,

Tzerne, were forced by the Russians to leave Panemune and live in

Rostov until the end of the war.

[13]

Kagan, (Op. Cit.), states that 9,000 out of 20,000

Kovno Jews returned at this time.

[14]

This inference is based on known statistics for Kovno.

In 1923, 25,000 Jews were now found in Kovno, versus 40,000

in 1915.

[15]

See 1921 Census of Poland; Landsmen, Vol. 9, Numbers 2-3, June,

1999, p. 13. The Blackbook of Localities Whose Jewish

Population was Exterminated by the Nazis, (Yad Vashem,

Jerusalem, Israel, 1965, "A. Panemune") stated that in 1921 there

were 18 Jewish families. If each family numbered 4 children, this

would correlate with the 1921 census numbers.

[16]

(See Kagan,

Yidishe Shtet, p. 382.)

[17] 1925 tax list of Panemune Jewish community, Lithuanian Kehilot collection, "Panemune", YIVO.\

[18] See Jeffrey A. Marx, “Jewish Families and Individuals in Panemune 1800-1941”, http://kehilalinks.jewishgen.org/Aukstoji_Panemune/index.htm, 1/28/2012.

[19]

See 1843 Tax Report of Panemune Jewish Community (Op. Cit.) which

states that Yankiel Glattshtein had been employed since 1824 as a

shames; Panemune Death Registry, 1826-1837).

[20]

See 1843-1845 correspondence from the Jewish Community of Panemune

to the Augustow Depts. of Religious Affairs and Industry, seeking

for reimbursement for funds expended in the rebuilding of the mikvah

and petitioning for additional money to replace its straw roof with

tiles. (Poniemon

Frentzela files, CWW 1835, AGAD, Warsaw).

[21]

See Prenumeranten List, Pardes HaBinah.

He was not, apparently there by 1843, as the 1843 Tax Report

(Op. Cit.) shows no rabbi in Panemune for that year.

[22]

Panemune Birth and Marriage Records were recorded as early as 1857

by the Kaunas and Viliampole rabbinate.

The majority of the marriages which involved Panemune’s

Jewish inhabitants are recorded as taking place in Kaunas between

1857 and 1922. Panemune

did have at least one rabbi during this time, Benjamin Meisels,

though it appears that certain events were, at the very least,

recorded by the Kaunas Jewish authoritites.

[23]

10/8/1857 blueprint: “Plan of the Wooden Synagogue Located in

Poniemonin” and “Plan of the Wooden Schul Located in Poniemonin”

(RAGAD, Warsaw, “Poniemon Frentzela” file, CWW 1861). The synagogue

was build just to the right of the schul.

[24]

One side of the cemetery bordered the river. The earliest

remaining gravestone found in the cemetery, is 1840.

In 1928, cement pillars bordered the cemetery.

After WWII, the cemetery was destroyed.

(Wolf Bregstein letter to Jeffrey A. Marx, 4/18/1987;

interview with Zalman Shaymes, 5/4/88; Horwich, Bernard, Op. Cit.).

It is probable that the Jews of Panemune were always buried

in the Panemune cemetery.

First of all, it would have been too cumbersome to transport

the body across the river.

Even if they had done so, the only Jewish cemetery in the

Kaunas area before 1862, was in Slobodka, on the other side of

Kaunas. This would have

been too long a distance to travel for burial.

(See Yahadut Lita, Vol. II, "Kovno", Op. Cit.).

The 1864 marriage registration of Judel Chaimowitz Bregstein

states that 3 announcements of his wedding had been made in the

Panemune synagogue.

Web Page: Copyright © 2009-2020 Jeffrey A. Marx